An interesting take on a WW II like economic mobilization to meet the depression threat in the current COVID crisis. From Barry Ritholtz, a liberal investment analyst, with a better than average forecasting record.

The economic crisis created by Covid-19 is unlike any other in modern American history. Thousands are dead, and the economic fallout has been devastating. More people lost their jobs over four weeks in March and April than did so during the entire 2008-09 financial crisis. In fact, since mid-March, all of the employment gains since the last crisis ended have been lost. Of the 156 million people the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics measured as working full time then, more than 26 million—about 16.7%—were no longer receiving a paycheck as of April 23. If you add in gig workers and those who were unable to file unemployment claims because state offices were too overwhelmed, the tally was more than 20%. At this pace, we will eclipse the peak of unemployment during the Great Depression, 25%, in a matter of weeks.

This sudden collapse in economic activity, hitting every sector except for food, health care, and Netflix, is why Congress moved quickly to pass the $2 trillion CARES Act on March 27. In late April, lawmakers added $320 billion to replenish the U.S. Small Business Administration's Paycheck Protection Program. That sounds like a lot, until you learn that the first allotment, $349 billion, lasted barely a week. CARES2, another trillion-dollar stimulus, is already under congressional consideration. CARES3 won't be too far behind.

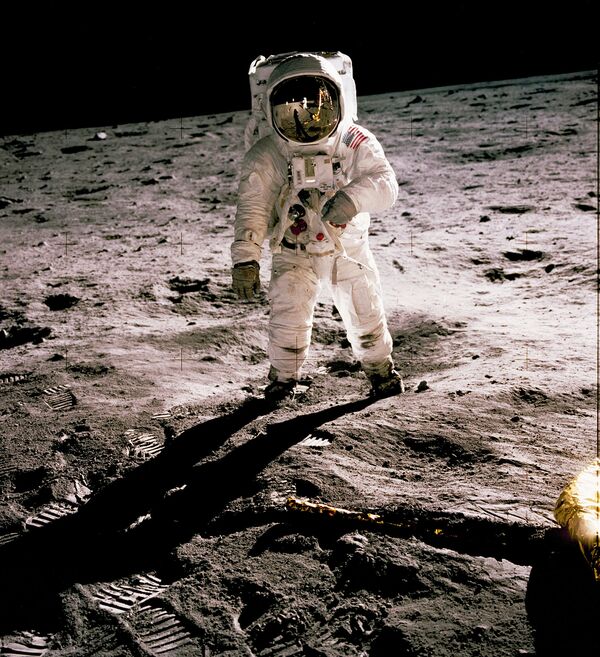

But these are all temporary salves, not long-term solutions. The current rescues only treat the symptoms of economic distress; they do nothing to address structural issues that have been a drag on middle-class household income since the 1980s. If we want to restart the engine that made this nation a superpower, we need to do something big. I mean really, really big: defeat-the-Nazis, land-a-man-on-the-moon, invent-the-internet big.

There's no small amount of irony in this coming from me. I'm the guy who wrote an entire book, Bailout Nation, arguing against bailouts for, among others, Chrysler in 1980, Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, and the failing banks of 2008-09.

But I'm not talking about a bailout. For generations, and most successfully in the Depression's aftermath, the U.S. has used public-private partnerships to drive the country's economic expansion, allowing entrepreneurs and innovative companies to take advantage of the long-term planning and financial strength of Uncle Sam. This strategy led to new industries and technologies, creating millions of good middle-class jobs in the process. This is the solution that must no longer be overlooked. What we need right now are public-private partnerships on a scale not attempted since the Depression.

When the stock market crashed in 1929, the Federal Reserve was a young institution with limited authority. Reviving the economy was the job of the White House and Congress. Programs such as the Works Progress Administration, in which the federal government hired workers to build more than half a million miles of streets and 10,000 bridges, along with airports, dams, highways, and sanitation systems, helped alleviate mass unemployment. However, the lasting economic gains came not from temporary work programs, but rather from the Reconstruction Finance Corp., a public-private entity better known as the RFC.

Louis Hyman, an economic historian and director of the Institute for Workplace Studies at Cornell, recently described RFC in the Atlantic as "an independent agency within the federal government that set up lending systems to channel private capital into publicly desirable investments. It innovated new systems of insurance to guarantee those loans, and delivered profits to businesses in peril during the Depression." Most impressive, as Hyman has noted, these programs cost taxpayers nothing.

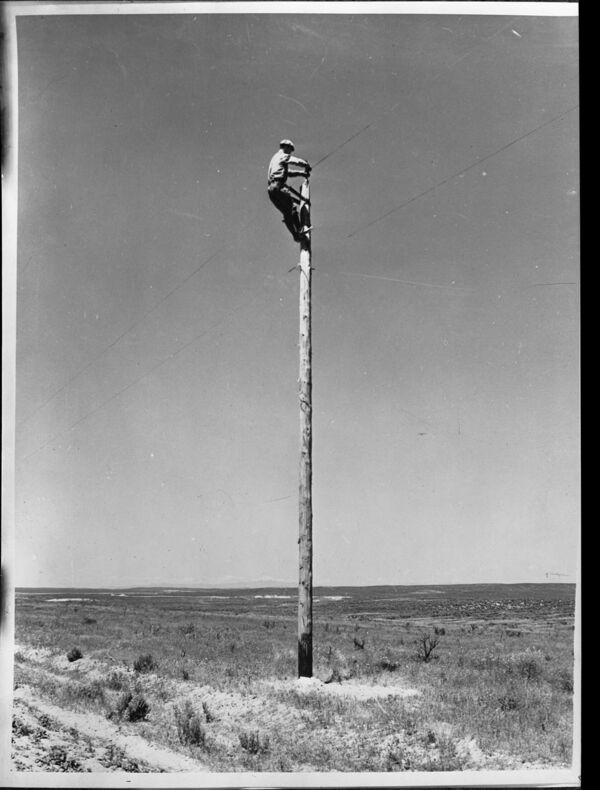

The Rural Electrification Administration helped finance thousands of miles of electrical wires to benefit farms and ranches.

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The RFC was an enormous economic multiplier. Start with the Depression-era breakdown of the banking system. That institutional collapse wasn't caused by a lack of capital; larger national banks such as National City Bank and Bank of America had idle cash. But low potential returns, combined with post-traumatic stress lingering from the stock crash, made bankers so risk-averse they wouldn't even lend to each other.

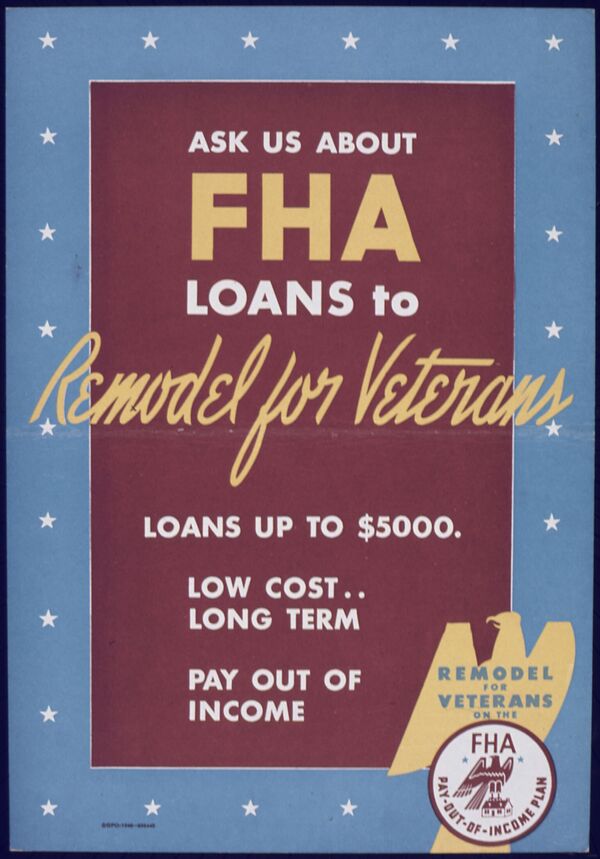

The RFC's solution in 1934 was for private bank employees to work with its subsidiary, the Federal Housing Administration, to create insurance for pools of mortgages. This led to a resurgence of financing for home purchases. Another RFC subsidiary, the Rural Electrification Administration, worked with farm cooperatives and banks to issue low-interest 20-year loans to run thousands of miles of electrical wires to rural farms and ranches—something the private sector had said would be too expensive.

During the years before World War II, the RFC created the Defense Plant Corp., offering loans and tax benefits for the manufacture of tanks, planes, and other weapons used by the Allies to fight the Nazis. The DPC helped add 50% to the country's manufacturing capacity by the war's end, according to Hyman. In 1940 it was responsible for 25% of the nation's entire gross domestic product. Hyman noted that it remade the U.S. aerospace and electronics industries, turning them into some of the largest sectors in the economy.

Half a century later, most Americans have forgotten all that these public-private partnerships accomplished—to such an extent that there is political hay to be made by demonizing government programs of any kind. We've lived off their fruits while failing to establish new programs. This void has led to a list of structural issues: underemployment, an increasing wage gap, a lack of household savings, and a looming retirement crisis.

By the time the Great Recession arrived in the late aughts, Congress resisted the idea of a big stimulus plan. That was, until Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke informed them the nation was "days away from a complete meltdown of our financial system," as then-Senator Christopher Dodd later recounted. Even then, lawmakers didn't do all that much, passing the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, which was later reduced to $431 billion, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion plan that included short-term benefit extensions and tax cuts.

While Congress dithered, the response of the U.S. central bank was unprecedented. The Fed fashioned dozens of programs to put $4 trillion into credit markets. This helped to unfreeze credit markets and allowed bank lending to occur. The Great Depression had FDR; the Great Recession had Ben Bernanke.

His actions were effective in a narrow sense: He saved the finance sector. The Fed's zero-interest-rate policy stopped 2/28 adjustable-rate mortgages—loans with teaser rates that shot higher after 24 months—from resetting, which prevented defaults. This gave banks time to gradually improve their balance sheets, but it planted seeds that led to a variety of unintended consequences.

Saving the banks turned out to be a boon to property owners, homebuilders, and the private equity funds that were investing in distressed real estate, who saw their holdings quickly recover their value. But those who didn't own homes, including many people who'd lost them to foreclosure, were turned into renters.

An FHA poster from the early 1940s. The Federal Housing Administration created insurance for pools of mortgages, which led to a resurgence of financing for home purchases after the Great Depression.

SOURCE: NARA

Investors did well, of course. If you still owned stock in March 2009, when the market hit its lowest point—or better yet, if you had enough capital to buy more stock—your risk-taking was richly rewarded. From those lows, the S&P 500 tripled over the next few years. Even with the recent post-Covid correction, the index is still worth four times what it was in 2009.

Most Americans don't own much in stocks. In a 2017 study, Edward Wolff, a professor at New York University and researcher at the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that the wealthiest 10% of U.S. households owned 84% of all stocks. During the recovery, the wealthiest segments of society got wealthier. I should disclose that I benefited from it personally, too. My firm, Ritholtz Wealth Management, manages more than a billion dollars in stocks and bonds. Our clients did well in part because their portfolios have benefited dramatically from rising prices. The Fed deserves credit for some of that increase in asset values.

Another enormous windfall went to those employees who had lots of company stock options. From October 2007 to March 2009, the S&P 500 fell 56%. Many companies, including Apple, Starbucks, and Google, allowed their employees to trade in worthless stock options for new ones with much lower strike prices in 2009. The biggest beneficiaries were the executives who held the lion's share of issued options. As the market and the economy recovered thanks in part to the Fed's monetary efforts, these options became deep in the money. Tens of millions of dollars in risk-free profit were created for some already wealthy people.

While the financial sector recovered, Congress did little to help the rest of the economy. In the past, when household and private-sector demand collapsed, the government stepped in to replace it by spending more and cutting taxes. For reasons people still debate—ideology? deficit concerns? partisanship?—the fiscal response in 2009 was sorely lacking.

As people began to find new jobs, they were often worse than the ones they'd lost during the crisis—with lower wages and fewer (if any) benefits. Without a substantial fiscal stimulus, the good middle-class jobs associated with large public works projects or civil service employment never materialized. Gains from the economic recovery never "trickled down" to the working classes.

The 2020 economic rescue has skimmed from the responses to both the Great Depression and the Great Recession. But so far it's been heavily slanted toward the latter approach, as the Fed has slashed interest rates to zero and committed more than $2 trillion to keep rates low and credit markets liquid. The $2 trillion CARES Act aims to replace income and spending for those 92% of Americans under shelter-in-place orders until the crisis passes. Most of that CARES money will replace lost wages for employees of small and midsize businesses for a short while; the rest will cover lost revenue for a few larger businesses. There's also money going to states, cities, and hospitals.

The response has been more substantial than what the government did during the 2008-09 crisis. But it's still nowhere near enough.

We should be using RFC-like partnerships to build technological platforms and infrastructure for the future. The list of potential areas is long—but here are a few ideas:

① Climate remediation

Nine of the 10 warmest years in recorded history have occurred since 2005. What's been missing from the attempts to address global warming has been a comprehensive search for a huge technological solution to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or perhaps a series of smaller ones that cumulatively have a substantial impact. Accelerating this process could have implications for avoiding what might very likely be humanity's next great crisis.

② Sustainable energy

One reason for modest hope in the looming climate crisis has been incremental improvements in the efficiency of wind and solar energy, along with battery storage improvements. What we need to make this energy technology much more efficient would be a Manhattan Project of sorts, aiming for fundamental breakthroughs in both the science and the technology. The resulting cheap, abundant energy would help reduce future carbon emissions and pollution—and lower costs for energy-intensive businesses.

③ Infrastructure

The U.S. once had the world's leading roads, airports, and electrical grids. We have foolishly allowed these to fall into disrepair and decay. This lowers the quality of life, hurts economic growth, and puts America at a disadvantage to rising powers in Asia. The solution is to create a Reconstruction Infrastructure Corp. to prioritize projects for repair and rebuilding. Fund it with 50- to 100-year bonds issued at 2%. Infrastructure is more than a make-work program; it's the platform that allows businesses to operate efficiently.

④ Smart roads

Speaking of platforms, it's only a matter of time before self-driving cars are here. Greater traffic capacity, faster commutes, and reduced automobile fatalities will be the happy result. But whether this happens in a few years or, more pessimistically, a few decades is unclear. What would speed things along would be a uniform set of radio-frequency devices built into roads and vehicles to allow safe navigation regardless of weather or traffic conditions. A public-private partnership could (among other things) create a set of standards that allows different vehicle manufacturers to interact safely on the open road.

⑤ Digitized health care

How is it possible that in 2020 the flow of health-care information has yet to become seamless and universal? How is this crucial sector still operating as if it were the 19th century? Prior government attempts to address this issue have been too modest. Instead, combine the government's efforts with the health-care initiative created by Warren Buffett, Jamie Dimon, and Jeff Bezos—and create a bold, comprehensive experiment.

⑥ Asteroid mining

This isn't merely something out of science fiction. Serious technologists believe we could launch a fleet of unmanned ships to mine valuable minerals. I understand that some want to go to Mars. I say aim farther, all the way to the asteroid belt, with its vast riches of industrial metals, nickel, cobalt, and likely gold and platinum.

In all of those examples, the journey is the reward. Landing a man on the moon was a triumph of ingenuity, but the economic benefits came from the technology that the Apollo program developed. Integrated circuits, fireproof materials, water purification, freeze-dried food, polymer fabrics, cordless tools—the list is so long that we take it for granted. We need to update President Kennedy's challenge, not for the national glory, but for the societywide economic benefits.

Buzz Aldrin walks on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

SOURCE: NASA

Some will say what I'm arguing for here would be a departure from 21st century U.S. political and economic realities. But as entrepreneur and author Bhu Srinivasan points out in Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism, Uncle Sam has successfully partnered with the private sector throughout our history, creating exclusive monopolies through patent protections and municipal bonds, among many other innovations. Or, to quote the venture capitalist William Janeway, the U.S. innovation economy has always been "sponsored by the state and funded by speculation."

It sometimes takes a crisis to get past the usual partisan wrangling in Congress. Right now there's a rare willingness to try more short-term stimulus. But the lesson of the past two centuries is that to benefit the U.S. population, the government needs to enact a long-lasting fiscal stimulus—a new NASA, not just an extra few hundred dollars to get us through the next few months.

Grover Norquist once said his goal for government was "to get it down to the size where we can drown it in the bathtub." It's a great punchline, right up until you need the government to fight the Nazis—or to control a global pandemic that threatens to kill millions and destroy the economy.

Time will tell if this White House and Congress are up to this enormous task. The public gets to grade the response and rescue plan in about six months—on Nov. 3.

This is no time for thinking small. America, confronted with the biggest crises, has always stepped up. We face yet another historic crisis. Once again it is time for America to go big.

Barry Ritholtz is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist and the author of Bailout Nation: How Greed and Easy Money Corrupted Wall Street and Shook the World Economy. He is the founder of Ritholtz Wealth Management.

-- via my feedly newsfeed