Friday, March 31, 2017

Enlighten Radio:Podcast: Labor Beat -- Medical Cannabis--Phoenix from the WV Legislative Train Wreck

John Case has sent you a link to a blog:

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Podcast: Labor Beat -- Medical Cannabis--Phoenix from the WV Legislative Train Wreck

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/podcast-labor-beat-medical-cannabis.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Podcast: Labor Beat -- Medical Cannabis--Phoenix from the WV Legislative Train Wreck

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/podcast-labor-beat-medical-cannabis.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Bernstein: Up for a little meta-discussion of tax policy? I thought so… [feedly]

Up for a little meta-discussion of tax policy? I thought so…

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/up-for-a-little-meta-discussion-of-tax-policy-i-thought-so/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

So, with those ground rules in place, and with the recognition that "we" is a tricky word in today's polity, let's think about what we want our tax system to accomplish.

• It must raise ample revenue for the public sector to meet the challenges that the private sector won't address. Markets fail, and markets are incomplete. No private business will provide optimal levels of public goods and services such as education, transportation, health care and retirement security, global protection (both defense and climate), the justice system, labor and financial market oversight, and anti-poverty and countercyclical policies (not a complete list, I'm sure, but you get the idea). What that revenue level should be is of course the hard part, but let me resort to averages, which if not a systematic, bottom-up calculus, at least reveals how we've answered this question historically.

Since 1970, the federal revenue share of the gross domestic product has averaged 17.4 percent, ranging from around 15 to 20 percent. It's just under 18 percent today. Congressional Budget Office analysis reveals that meeting the promises of Social Security and Medicare would require about 2.5 percentage points more than that by 2027. That takes us slightly past the upper bound of the historical record, but the extent of our aging demographics is historically unique.

In other words, revenue neutrality is an insufficient goal. Tax reform — meaning changes in revenue dictated by needs and obligations — should be revenue positive.

• We can argue whether a tax system should reduce market inequalities — based on non-merit-based inequalities embedded in the market economy, I think it should — but I know no cogent argument for why tax changes should be dis-equalizing. Yes, you still hear about "trickle-down": give the rich a tax break and they'll create opportunity for everyone else. But as noted, this is nothing but a fact-free rationale for regressive tax cuts. I'm probably being too optimistic, but I sense that people increasingly know this, and that the politicians who sell this snake oil are starting to sense that maybe the people are on to them.

• We want a tax code that does not distort people's behaviors too much, although it's easy to overdo these concerns. There are many different types of tax systems around the globe, and at the end of the day they don't have nearly the impact on people's willingness to work, invest, move, trade, and so on that the noise from this part of the debate would lead you to believe.

So we want a tax system that will raise ample revenue without worsening pretax inequality, in which "ample" means enough to meet the functions in the list above.

I'm sure there are readers who think that by dint of arguing for more revenue, I've punted on objectivity and tilted in support of more government. I disagree. Unless what you're saying is, "No, we don't need or want as much Social Security, Medicare, schools, roads, police, armies and so on as we already have," you either have to agree with me or explain to me where we get the money. If your answer is cut waste, fraud, abuse and foreign aid, you're not being serious.

If your answer is, "We can't afford all the above and must cut them," I disagree, but at least you're consistent. You are, however, out of step with most Americans who want what's on that list, and it's very important to recognize that they're not being unreasonable: These are things provided by governments in every advanced economy — again, for good reason. They are public goods.

I urge you to keep all this in mind during the forthcoming tax debate, although I warn you that to do so is to reveal the complete nonreality of that debate. I hope you're not allergic to cognitive dissonance.

Jared Bernstein

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/up-for-a-little-meta-discussion-of-tax-policy-i-thought-so/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Last week in Washington, we were all abuzz about health-care reform. Now we're all abuzz about tax reform. Our problem — one of our problems — is that all the buzzing crowds out rational thought. An objective look at the reality of today's economy, our demographics and our income distribution suggests that the current tax debate is terribly misguided.

I suspect I'm shouting into a void here, but that's never stopped me: The nation does not need and most of us don't want a big, regressive tax cut. Yet despite claims to the contrary, that's what we're likely to see at the end of this benighted process.

An objective look at the questions posed by tax reform requires both sides to banish some shibboleths. For Republicans, this means dropping the assumption that tax cuts are always and everywhere desirable, as they generate more economic activity and shrink government. Neither of those claims are anywhere close to true, as there's no empirical correlation between tax cuts on the wealthy or businesses and favorable, lasting economic outcomes. Neither do tax cuts shrink government, as tax-cutting policymakers are happy to use deficit spending to replace revenue losses.

Also, the increasing tendency of Republicans to engage in reverse Robin Hoodism — paying for huge breaks for the wealthy by raising taxes or cutting spending on the poor — in an economy that generates too much inequality before taxes kick in is unjust and terrible policy.For Democrats, it means abandoning the notion that we can have everything we want and send the bill to the top 1 percent, and accepting that the corporate tax system is a hot mess that needs repair.

Yes, the rich disproportionately benefit from pretax growth and, in a progressive system, should not be shielded from paying more taxes. Ideas such as getting rid of the estate tax are preposterous saps to the superwealthy for no other reason than to do their bidding. But "get it from the rich" can't be the extent of every Democratic tax plan.

The statutory corporate tax rate — at 35 percent — is among the highest among advanced economies, but because of all the loopholes the effective rate is at least 10 points lower. This creates a strong incentive for special treatment, and these carve-outs are a function not of thoughtful policy but of the skills and connections of your lobbying team. There is some bipartisan consensus to lower the rate while maintaining at least revenue neutrality by closing the loopholes, but the problem is always that the lobbyists are very good at protecting their turf

I suspect I'm shouting into a void here, but that's never stopped me: The nation does not need and most of us don't want a big, regressive tax cut. Yet despite claims to the contrary, that's what we're likely to see at the end of this benighted process.

An objective look at the questions posed by tax reform requires both sides to banish some shibboleths. For Republicans, this means dropping the assumption that tax cuts are always and everywhere desirable, as they generate more economic activity and shrink government. Neither of those claims are anywhere close to true, as there's no empirical correlation between tax cuts on the wealthy or businesses and favorable, lasting economic outcomes. Neither do tax cuts shrink government, as tax-cutting policymakers are happy to use deficit spending to replace revenue losses.

Also, the increasing tendency of Republicans to engage in reverse Robin Hoodism — paying for huge breaks for the wealthy by raising taxes or cutting spending on the poor — in an economy that generates too much inequality before taxes kick in is unjust and terrible policy.For Democrats, it means abandoning the notion that we can have everything we want and send the bill to the top 1 percent, and accepting that the corporate tax system is a hot mess that needs repair.

Yes, the rich disproportionately benefit from pretax growth and, in a progressive system, should not be shielded from paying more taxes. Ideas such as getting rid of the estate tax are preposterous saps to the superwealthy for no other reason than to do their bidding. But "get it from the rich" can't be the extent of every Democratic tax plan.

The statutory corporate tax rate — at 35 percent — is among the highest among advanced economies, but because of all the loopholes the effective rate is at least 10 points lower. This creates a strong incentive for special treatment, and these carve-outs are a function not of thoughtful policy but of the skills and connections of your lobbying team. There is some bipartisan consensus to lower the rate while maintaining at least revenue neutrality by closing the loopholes, but the problem is always that the lobbyists are very good at protecting their turf

So, with those ground rules in place, and with the recognition that "we" is a tricky word in today's polity, let's think about what we want our tax system to accomplish.

• It must raise ample revenue for the public sector to meet the challenges that the private sector won't address. Markets fail, and markets are incomplete. No private business will provide optimal levels of public goods and services such as education, transportation, health care and retirement security, global protection (both defense and climate), the justice system, labor and financial market oversight, and anti-poverty and countercyclical policies (not a complete list, I'm sure, but you get the idea). What that revenue level should be is of course the hard part, but let me resort to averages, which if not a systematic, bottom-up calculus, at least reveals how we've answered this question historically.

Since 1970, the federal revenue share of the gross domestic product has averaged 17.4 percent, ranging from around 15 to 20 percent. It's just under 18 percent today. Congressional Budget Office analysis reveals that meeting the promises of Social Security and Medicare would require about 2.5 percentage points more than that by 2027. That takes us slightly past the upper bound of the historical record, but the extent of our aging demographics is historically unique.

In other words, revenue neutrality is an insufficient goal. Tax reform — meaning changes in revenue dictated by needs and obligations — should be revenue positive.

• We can argue whether a tax system should reduce market inequalities — based on non-merit-based inequalities embedded in the market economy, I think it should — but I know no cogent argument for why tax changes should be dis-equalizing. Yes, you still hear about "trickle-down": give the rich a tax break and they'll create opportunity for everyone else. But as noted, this is nothing but a fact-free rationale for regressive tax cuts. I'm probably being too optimistic, but I sense that people increasingly know this, and that the politicians who sell this snake oil are starting to sense that maybe the people are on to them.

• We want a tax code that does not distort people's behaviors too much, although it's easy to overdo these concerns. There are many different types of tax systems around the globe, and at the end of the day they don't have nearly the impact on people's willingness to work, invest, move, trade, and so on that the noise from this part of the debate would lead you to believe.

So we want a tax system that will raise ample revenue without worsening pretax inequality, in which "ample" means enough to meet the functions in the list above.

I'm sure there are readers who think that by dint of arguing for more revenue, I've punted on objectivity and tilted in support of more government. I disagree. Unless what you're saying is, "No, we don't need or want as much Social Security, Medicare, schools, roads, police, armies and so on as we already have," you either have to agree with me or explain to me where we get the money. If your answer is cut waste, fraud, abuse and foreign aid, you're not being serious.

If your answer is, "We can't afford all the above and must cut them," I disagree, but at least you're consistent. You are, however, out of step with most Americans who want what's on that list, and it's very important to recognize that they're not being unreasonable: These are things provided by governments in every advanced economy — again, for good reason. They are public goods.

I urge you to keep all this in mind during the forthcoming tax debate, although I warn you that to do so is to reveal the complete nonreality of that debate. I hope you're not allergic to cognitive dissonance.

Alex Tuckett: Does productivity drive wages? Evidence from sectoral data

This is an bit wonky of an article, but, there is no unsolved question in Economics that is bearing down harder on effective economic policy-making and planning than the slowdown in US productivity. Expectations ran high from the miracles of the high tech revolution, automation, health science and space travel that a boom in creativity and value-creating labor comparable to the deployment of steam technology in the era of industrialization was imminent. Not so, or, nowhere near expectations anyway.

This article explores several aspects of the question.

1. In the LONG RUN there is a strong correlation between wages and productivity. "LONG RUN" -- think decades and scores of years. Also, remember "productivity" is a rate of increase in production per unit of labor (usually calculated in hours). Productivity is obviously closely related to overall economic growth. Produce more with less cost, especially time cost. Population is usually growing, so a rate of economic growth greater than that generated by population growth alone is necessary to increase overall wealth, per capita The data series analyzed by Alelx Tucket sustain a definite correlation, but a multi-dimensional one.

2. The article points out a very important aspect of the relationship between increased productivity and increased wages. The relationship is two-way. In other words, in labor movement vocabulary, the rise in technology demands increased demand for new skills in the labor market, which puts pressure on the labor market -- assuming there is not mass unemployment at the time! But the social struggle of workers for higher wages and benefits was itself a driver of investment by business in labor saving technologies.

The article does not address the large debate about how to measure productivity. However, when you consider valuing commodities like software and other intangible products or services, an unknown, but probably large, missing component in reported data is the cost of theft arising from the relative ease at which products of immense "value" -- say the source code for Microsoft Windows Operating System for example -- can be copied, carried out the door on a thumb drive, in some cases. Thus millions of copies were freely copied in China. That degrades the products economic value, and thus the measured productivity of its creators.

The article skips the rather large social and political narratives that are inseparable companions of any structural -- and many incremental -- economic changes required to either deploy technologies throughout an economy, or to establish institutions of social security, justice, labor rights and protections, or to educate and reeducate new workforces for new occupations and new divisions of the work of society.

Does productivity drive wages? Evidence from sectoral data

Alex Tuckett

Since 2008, aggregate productivity performance in the UK has been substantially worse than in the preceding eight years. Over the same period, aggregate real wage growth has also been significantly lower – it has averaged -0.4% per annum from 2009-16, compared with 2.3% per annum from 2000-08. The MPC, and others, have drawn a link between these two phenomena, arguing that low productivity growth has been a major cause – if not the major cause – of weak wage growth. The logic is simple – if workers produce less output for firms, then in a competitive market firms will only be willing to employ them at a lower wage.

However, wages undershot forecasts before the crisis (Saunders, 2017), and alternative reasons have been advanced for slow wage growth: developments in labour supply, which may have lowered the natural rate of unemployment, or low headline inflation. A careful analysis of the sectoral data suggests that the relationship between productivity and wages is not simple, and that causality may run in both directions.

The slowdown in productivity performance has been uneven across sectors (a recent BU post offers readers an interactive tool that can be used to explore sectoral productivity trends). A number of sectors, such as agriculture and construction, have actually seen productivity growth accelerate. Can the dispersion of productivity performance across industries tell us anything about the link between productivity and wages?

Economic theory argues that the marginal product of labour is the most important determinant, in the long-run, of wages. Average output per worker is only an imperfect guide to marginal product, but over the very long term, aggregate productivity and wages have indeed moved closely together (Haldane, 2015). However, perhaps surprisingly, economic theory does not necessarily predict a strong link between productivity in any particular industry and wages in that industry. If labour can move freely between sectors, then productivity growth in one particular industry will result in slightly higher wages for the workforce in general, not just workers in that industry. What matters for wages is the outside option for workers – which in turn is determined by productivity in the economy as a whole.

In reality, moving between sectors can involve time, money and taking a risk. Furthermore, the picture is complicated because productivity changes can be 'passed forward' into prices as well as 'passed backwards' into wages.

To investigate the link between wages and productivity empirically, ONS data on sectoral output can be combined with data on sectoral wages and employment from the Average Weekly Earnings (AWE) survey. Together, these data give a picture of the joint behaviour of productivity and wages across 24 industries in the economy.

This level of disaggregation is more detailed than the 16 industry split published in the Quarterly National Accounts (QNA); manufacturing is split into 6 industries, whilst on the service side, wholesale and retail are separated, as is transport from communications. Data quality at lower levels of aggregation is likely to be slightly worse; however the results are similar using the smaller set of industries defined in the QNA.

The AWE employment data do not include self-employment, which will bias the calculations of productivity slightly for some industries in which self-employment is important. This is likely to be more of an issue for the level of productivity than the growth rate.

These data can be used to answer a number of questions:

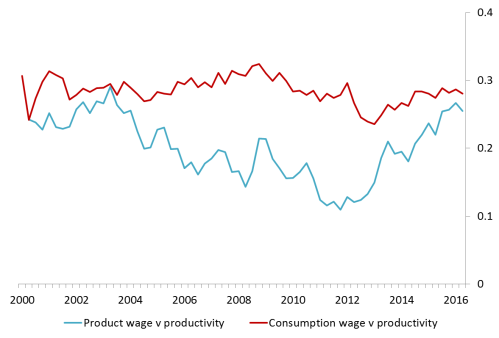

Do industries with high productivity also have high wages?

Yes. Figure 1 shows the correlation across industries between log real output per worker and log average real wages. The red line shows the correlation between real productivity and real consumption wages (RCW). Real consumption wages are nominal wages from AWE deflated by the aggregate CPI; they try to measure what a wage is worth in terms of the goods and services it can purchase. The blue line shows the correlation of productivity with real product wages (RPW). RPW are nominal wages deflated by the price deflator for that industry, and try to measure the cost of labour to the firm in terms of the goods or services the firm produces. The correlation between productivity and wages has been positive at all times for both measures.

Figure 1: Correlation across industries between the level of productivity and average pay

Source: ONS, author's calculations. Excludes manufacture of textiles, leather and clothing; for this industry, the deflator increases very sharply (by around 40%) over 2012 and 2013, abruptly increasing the RPW-productivity correlation. Given the problems with the measurement of clothing and footwear prices this is likely to be at least partly spurious.

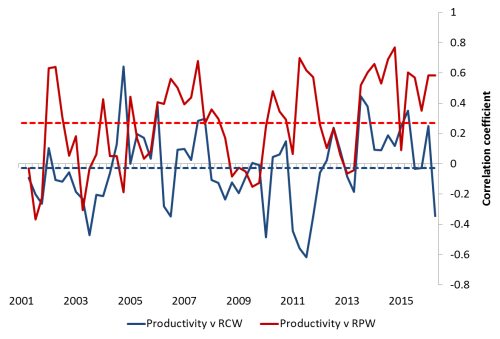

Do industries with higher productivity growth have higher wage growth?

Productivity growth can vary considerably across industries. Even excluding mining and extraction (the industry with the most volatile productivity by far), the cross-sectional standard deviation of annual growth averages around 6 percentage points although it has been trending downwards. At any one time, productivity can be growing fast in one industry whilst stagnating (or contracting) in another.

Do these industry-specific variations in productivity growth feed through into real wage growth? That depends on the measure. As the blue line in Figure 2 shows, there is little or no reliable correlation between growth in productivity and RCW (the chart shows the correlation for annual growth rates, but the results are similar using higher or lower frequency measures).

There is a much better industry-level correlation between growth in productivity and RPW (the red line in Figure 2). Although not stable, the correlation is positive in most periods and averages 0.25. The beta in a cross-sectional regression of productivity on RPW has averaged about 0.33; that is, a 1% increase in productivity growth is associated with an increase in RPW of around 0.3%. The value of this coefficient has been trending up over time.

Figure 2: Correlation between annual growth (quarter on quarter of previous year) in productivity and real wages

Source: ONS, author's calculations. Excludes manufacture of textiles, leather and clothing.

RPW growth is also better correlated with productivity growth at an aggregate level. That suggests that RCW growth is moved around by factors other than productivity – for instance, movements in the exchange rate that affect retail prices – and so points to a limited role for 'real wage resistance' (the idea that increases in living costs from higher import prices will lead workers to bid up nominal wages to support the real value of their earnings). The cross-sectional evidence supports the idea that it is output prices, not retail prices, which matter for wages.

These correlations may also tell us something about how an increase in productivity in a particular industry feeds through into real wages. Rather than bidding up relative nominal wages (and therefore, the relative RCW in that industry), an increase in productivity leads to lower relative prices for the output of that industry, increasing RPW for given nominal wage. This boosts the real consumption wages of workers in all industries. The benefits of productivity gains are diffuse; the costs, of course, may not be, if productivity gains lead to lost employment in that industry.

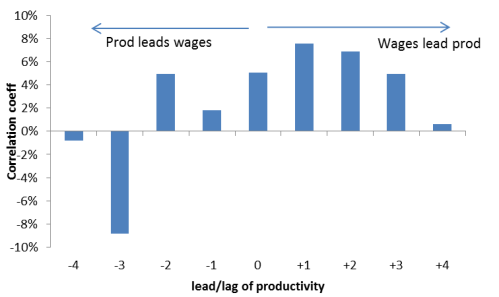

Does productivity growth help predict wage growth at an industry level?

Not really, no. The distribution of productivity growth across industries is positively correlated with subsequent wage growth – industries with higher productivity growth now will tend to have higher wage growth in subsequent quarters. However, productivity growth has little additional value in predicting wage growth over and above univariate models. Figure 3 shows the results from correlating industry level productivity shocks with wage 'shocks' (defined as the residuals from a univariate regression, with lag-structure chosen to optimise information criteria). The link between where an industry is in the current distribution of productivity growth and where it will be in the future distribution of wage growth is not very reliable. If anything, it is relative wage growth that tends to lead relative productivity growth.

Figure 3: Cross-industry correlation between shocks to productivity and lags, leads of wages

Average correlation from 2000Q1-16Q3 for each lead/lag combination, between shocks to productivity and to wages. Shocks are estimated as the residuals from a univariate regression, with lags chosen to optimise information criteria.

Looking at each industry in turn, Granger causality tests do not find a clear role for productivity growth in predicting wage growth. As shown in Figure 4, productivity growth Granger causes wage growth for only a minority of industries. Wages Granger-cause productivity for a larger group of industries, although still fewer than half.

Figure 4: Two–way Granger causality tests between real productivity and RPW at industry level

P-values: averages across industries for the test of whether lags of productivity (wages) have a joint coefficient of zero when added to a regression of wages (productivity) with lags of dependent variable. Proportions show share of industries with p-values below 10% (5%); e.g. using 6 lags, we can reject the null hypothesis that wages do not Granger cause productivity for 29% of industries.

Together, both cross-sectional and within industry time-series evidence are consistent with a two-way relationship between wages and productivity. There may be shocks from labour supply – or developments in other industries – which first affect wages, leading industries to adapt (for instance, change capital intensity) in a way that changes productivity. Alternatively, shocks to the demand for an industry's output could initially move wages, followed by a productivity response.

Conclusions

Rather than a simple and clean link from productivity to wages, the industry level data point to a richer and more multi-directional relationship between productivity and wages. Productivity growth is linked to wages, but the relationship may go both ways, and the link between productivity and real wages may operate through prices as much as nominal wages.

Alex Tuckett works the Banks external MPC unit.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

John Case

Harpers Ferry, WV

Harpers Ferry, WV

The Winners and Losers Radio Show

7-9 AM Weekdays, The EPIC Radio Player Stream,

Sign UP HERE to get the Weekly Program Notes.

Check out Socialist Economics, the EPIC Radio website, and

Krugman: Coal Country Is a State of Mind [feedly]

jcase: Apologies for no text on this one -- NYT no longer permits copying text. But there should not be paywall on the article

I am beginning to think Krugman should give up on politics. One does not have to conjure up a mass "nostalgia" for a vanished past to explain coal/natural gas influence in the West Virginia. It turns out that it does not matter if only 4% of the workforce is related to mining when 15-20% of the state revenue is from a coal and gas severance tax on extracted resources. The tax buys the continued dominion of natural resource industries over state government, which is highly centralized in West Virginia from a 100 year legacy of subordination to coal interests.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/31/opinion/coal-country-is-a-state-of-mind.html

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Enlighten Radio:Treeman and Ms Sustainable Shepherdstown Return to Paris, WV Rs shoot Pot

John Case has sent you a link to a blog:

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Treeman and Ms Sustainable Shepherdstown Return to Paris, WV Rs shoot Pot

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/treeman-and-ms-sustainable.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Treeman and Ms Sustainable Shepherdstown Return to Paris, WV Rs shoot Pot

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/treeman-and-ms-sustainable.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Thursday, March 30, 2017

Enlighten Radio:Revolution Radio Begins at 9 AM this Morning

John Case has sent you a link to a blog:

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Revolution Radio Begins at 9 AM this Morning

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/revolution-radio-begins-at-9-am-this.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Revolution Radio Begins at 9 AM this Morning

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/revolution-radio-begins-at-9-am-this.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

On Populism, Nationalism, Babies and Bathwater [feedly]

On Populism, Nationalism, Babies and Bathwater

http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/28/03/2017/populism-nationalism-babies-and-bathwater

-- via my feedly newsfeed

http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/28/03/2017/populism-nationalism-babies-and-bathwater

On Populism, Nationalism, Babies and Bathwater

Duncan Green - 28th March 2017Ducan Green shares some thoughts on recent discussions over how the aid sector should repond to the rising tide of nationalism, populism, and attacks on aid.

A couple of Oxfamers were over from the US recently so ODI kindly pulled together a seriously stimulating conversation about life, theuniverse and everything. More specifically, how should 'we' – the aid community broadly defined – respond to the rising tide of nationalism, populism, and attacks on aid. It was Chatham House rules, so I've already told you too much, but here are some of the highlights:

North v South: The traditional focus of international development NGOs has been the 'Global South' (although North-South distinctions have become increasingly dubious). Should that now change? Some people stressed that we need to focus more on politics in the North, both because the risks to progressive values that we used to consider the consensus are now very real. In the UK 'the winning side (on Brexit) is starting to change the minds of the losing side' – people who weren't bothered about immigration before now accept that it is 'an issue'. 'Ethics are like a muscle – they have to be exercised regularly or they will atrophy'.

There is also an instrumental argument: 'we need to invest in the North, or we'll lose the ability to have impact in the South.' Specifically 'we need to spend less time on policy and more on shaping public debate.'

In addition, maybe the current turmoil could provide the 'window of opportunity' to do more to refocus the long term agenda on promoting local control, stewardship, ownership etc, including giving higher priority to domestic taxation and the social contract between citizens and state.

Universalism v Nationalism: I was struck by how many people take the SDGs seriously as a symbol that we have moved beyond North-South to universalism, in which issues like rights, inequality and climate change are truly shared. But there was some fascinating scepticism in the room about how far 'we' can shift to a truly universalist approach. 'Aren't we part of the 1945-2015 consensus (on the division of the world into North and South)? Don't we just need to get out of the way and let a new generation of people and organizations move towards universalism?' That resonated with me, because I have seen just how hard it is for NGOs to move beyond a North-South frame in which the people we help are hungry, rural, oppressed and a long way away. Oxfam has been about to go urban since the late 1980s, according to successive strategic plans (thanks John Magrath for doing the digging on that!). It is very hard for development organizations to start working on shared agendas on tobacco, road traffic or obesity, however important they may be, simply because they fall so far outside our traditional narrative of what matters in developing countries.

Hug Populism, reject it or prepare for its collapse? 'We have fundamentally miscalculated our fellow citizens' in assuming a progressive consensus existed on at least some issues. What next? First, there is a risk of over-reacting – people have multiple identities bubbling away, and at different times, different ones come to the fore. We should still appeal to the better angels of people's natures because those angels are still there.

But is it better to respond to rising nationalism by engaging with it, trying to understand it better, building bridges with some elements within it etc, or is that a fool's errand in which we are forced to abandon principles and cross red lines with very little to show for it? Elements of the progressive agenda (inequality, industrial policy) feature in the populist rhetoric (if not their practice) so should we try and reclaim them for the progressive cause or pick other battles? In any case, what if the populist tide is peaking, shortly to come crashing down amid economic and political chaos? If so, wouldn't it be better to start preparing messages, alliances, ideas etc in advance so that we are as ready as possible for that historical critical juncture when it comes?

Aid: and then there's aid. We met the day after President Trump recommended a 28% cut in US aid, so

understandably we kept coming back to it. People contrasted 2015 and 2017. 2015 = an illusion of consensus, everyone debating the content of the SDGs; an 'end of history' moment when all that was required was better data. Fast forward two years and there is a 'relentless assault' on both sides of the Atlantic. When aid gets attacked, out of both self interest and commitment to the aid project, aid organizations spring to its defence. But isn't that one reason why they are the wrong ones to lead on universalism? And anyway 'whenever we try and move 'beyond aid', we do so by doing things through aid'. Ouch.

Overall, I was left confused and concerned (doubtless the mark of a good conversation). Concerned that the development community could jump into current northern battles on populism, Brexit etc not primarily because doing so is vital to helping the world end poverty in the long term, or because the issues that matter have suddenly become universal, but because the values of northern activists push them to get involved for personal reasons. If that happens, we risk forfeiting our legitimacy, which in the eyes of northern publics and policy makers is rooted in our links with and understanding of events in the South. And what do we gain if 'Going Northern' doesn't add much to the existing progressive forces in the North?

And although many issues like equal rights, inequality etc are universal, some things (like famine) are not. There are still huge differences between rich and poor people and countries, and that matters. Take fragile and conflict–affected states – you simply can't equate what goes on in rich countries and events in places such as Yemen or Somalia: perhaps unfortunately, they are the likely future of the aid industry, simply because more stable countries will graduate through a combination of growth, poverty reduction and rising taxation. Whatever we do in the North, we need to ask ourselves whether it is relevant and helpful to the communities in those places. If the answer is 'not really', we should worry about that.

I'm now stuck in a global confab of Oxfam big cheeses on similar subjects – will report back on anything new that emerges.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)