They filed with just 30% ("more than 2000"/7K), why? To get an voter list? Or do they think they can gain that much in the middle of Amazon's ramped up union busting campaign?On Thursday, October 21, 2021, 06:55:50 AM EDT, John Case <jcase4218@gmail.com> wrote:Amazon Staten Island Warehouse Workers in Push to Unionize

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-21/amazon-warehouse-workers-in-staten-island-push-to-unionizetext only:More than two thousand workers at four Amazon.com Inc. facilities in Staten Island have signed a petition asking federal labor officials to greenlight an election to form a new union, the latest spasm of labor strife between the e-commerce giant and its large blue-collar workforce.

The newly formed Amazon Labor Union must submit signatures from 30% of the workers to meet federal requirements. The facilities on Staten Island employ approximately 7,000 people. The National Labor Relations Board will determine whether the organizers have met the threshold to hold an election.

"We intend to fight for higher wages, job security, safer working conditions, more paid time off, better medical leave options and longer breaks," the Amazon Labor Union said Thursday in a statement.

The group's president, Christian Smalls, worked for Amazon for 4 1/2 years and was fired in 2020 after participating in demonstrations protesting the company's Covid-19 policies. Smalls alleged his firing was retaliatory, but Amazon said he violated safety guidelines.

The ALU has been organizing for the past six months, hosting barbeques and handing out water near Amazon warehouses in the New York borough. Organizers say Amazon has already been employing "union-busting" tactics to create doubt in workers' minds about the benefits of membership.

Amazon workers at a fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama, voted not to join a union in April. But the results were challenged, and a federal official recommended that the labor board hold a fresh election. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which led that campaign, alleged Amazon influenced the election by intimidating workers and pressuring them to cast votes in a mailbox the company had installed on its property in view of security cameras. Amazon denied any wrongdoing.

The Teamsters, whose members include delivery drivers for United Parcel Service Inc., are trying to organize Amazon warehouse workers in Canada.

The organizers of the union effort on Staten Island are bracing for pushback from the company. The first battle could come over which employees qualify for union representation, a classic tactic by employers looking to quash union elections.

The pandemic put a spotlight on the plight of so-called essential workers, including those in Amazon's logistics and delivery operations, whose labor helped many people reduce their exposure by having goods delivered to their homes. Growing public support for such workers has helped revive the hopes of U.S. laborSome Amazon warehouse workers in Europe belong to unions, but the company's vast logistics workforce in the U.S. isn't unionized. Amazon says its warehouse workers earn at least $15 hour -- a point it repeatedly hammered in Bessemer, where such wages go a lot further than they do in New York. However, union members working in transportation and warehousing earned 34% more than non-union workers in 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Friday, October 22, 2021

Re: Amazon Staten Island Warehouse Workers in Push to Unionize [feedly]

Thursday, October 21, 2021

Re: Amazon Staten Island Warehouse Workers in Push to Unionize [feedly]

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-21/amazon-warehouse-workers-in-staten-island-push-to-unionize

The newly formed Amazon Labor Union must submit signatures from 30% of the workers to meet federal requirements. The facilities on Staten Island employ approximately 7,000 people. The National Labor Relations Board will determine whether the organizers have met the threshold to hold an election.

"We intend to fight for higher wages, job security, safer working conditions, more paid time off, better medical leave options and longer breaks," the Amazon Labor Union said Thursday in a statement.

The group's president, Christian Smalls, worked for Amazon for 4 1/2 years and was fired in 2020 after participating in demonstrations protesting the company's Covid-19 policies. Smalls alleged his firing was retaliatory, but Amazon said he violated safety guidelines.

The ALU has been organizing for the past six months, hosting barbeques and handing out water near Amazon warehouses in the New York borough. Organizers say Amazon has already been employing "union-busting" tactics to create doubt in workers' minds about the benefits of membership.

Amazon workers at a fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama, voted not to join a union in April. But the results were challenged, and a federal official recommended that the labor board hold a fresh election. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which led that campaign, alleged Amazon influenced the election by intimidating workers and pressuring them to cast votes in a mailbox the company had installed on its property in view of security cameras. Amazon denied any wrongdoing.

The Teamsters, whose members include delivery drivers for United Parcel Service Inc., are trying to organize Amazon warehouse workers in Canada.

The organizers of the union effort on Staten Island are bracing for pushback from the company. The first battle could come over which employees qualify for union representation, a classic tactic by employers looking to quash union elections.

The pandemic put a spotlight on the plight of so-called essential workers, including those in Amazon's logistics and delivery operations, whose labor helped many people reduce their exposure by having goods delivered to their homes. Growing public support for such workers has helped revive the hopes of U.S. laborSome Amazon warehouse workers in Europe belong to unions, but the company's vast logistics workforce in the U.S. isn't unionized. Amazon says its warehouse workers earn at least $15 hour -- a point it repeatedly hammered in Bessemer, where such wages go a lot further than they do in New York. However, union members working in transportation and warehousing earned 34% more than non-union workers in 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Amazon Staten Island Warehouse Workers in Push to Unionize [feedly]

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-21/amazon-warehouse-workers-in-staten-island-push-to-unionize

The newly formed Amazon Labor Union must submit signatures from 30% of the workers to meet federal requirements. The facilities on Staten Island employ approximately 7,000 people. The National Labor Relations Board will determine whether the organizers have met the threshold to hold an election.

"We intend to fight for higher wages, job security, safer working conditions, more paid time off, better medical leave options and longer breaks," the Amazon Labor Union said Thursday in a statement.

The group's president, Christian Smalls, worked for Amazon for 4 1/2 years and was fired in 2020 after participating in demonstrations protesting the company's Covid-19 policies. Smalls alleged his firing was retaliatory, but Amazon said he violated safety guidelines.

The ALU has been organizing for the past six months, hosting barbeques and handing out water near Amazon warehouses in the New York borough. Organizers say Amazon has already been employing "union-busting" tactics to create doubt in workers' minds about the benefits of membership.

Amazon workers at a fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama, voted not to join a union in April. But the results were challenged, and a federal official recommended that the labor board hold a fresh election. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which led that campaign, alleged Amazon influenced the election by intimidating workers and pressuring them to cast votes in a mailbox the company had installed on its property in view of security cameras. Amazon denied any wrongdoing.

The Teamsters, whose members include delivery drivers for United Parcel Service Inc., are trying to organize Amazon warehouse workers in Canada.

The organizers of the union effort on Staten Island are bracing for pushback from the company. The first battle could come over which employees qualify for union representation, a classic tactic by employers looking to quash union elections.

The pandemic put a spotlight on the plight of so-called essential workers, including those in Amazon's logistics and delivery operations, whose labor helped many people reduce their exposure by having goods delivered to their homes. Growing public support for such workers has helped revive the hopes of U.S. laborSome Amazon warehouse workers in Europe belong to unions, but the company's vast logistics workforce in the U.S. isn't unionized. Amazon says its warehouse workers earn at least $15 hour -- a point it repeatedly hammered in Bessemer, where such wages go a lot further than they do in New York. However, union members working in transportation and warehousing earned 34% more than non-union workers in 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Monday, October 11, 2021

Cutting the reconciliation bill to $1.5 trillion would support nearly 2 million fewer jobs per year [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/cutting-the-reconciliation-bill-to-1-5-trillion-would-support-nearly-2-million-fewer-jobs-per-year/

Congress may have bought itself another month to negotiate over the Biden-Harris administration's Build Back Better (BBB) agenda, but one thing is clear: Further reducing the scale and scope of the budget reconciliation package unequivocally means the legislation will support far fewer jobs and deliver fewer benefits to lift up working families and boost the economy as a whole.

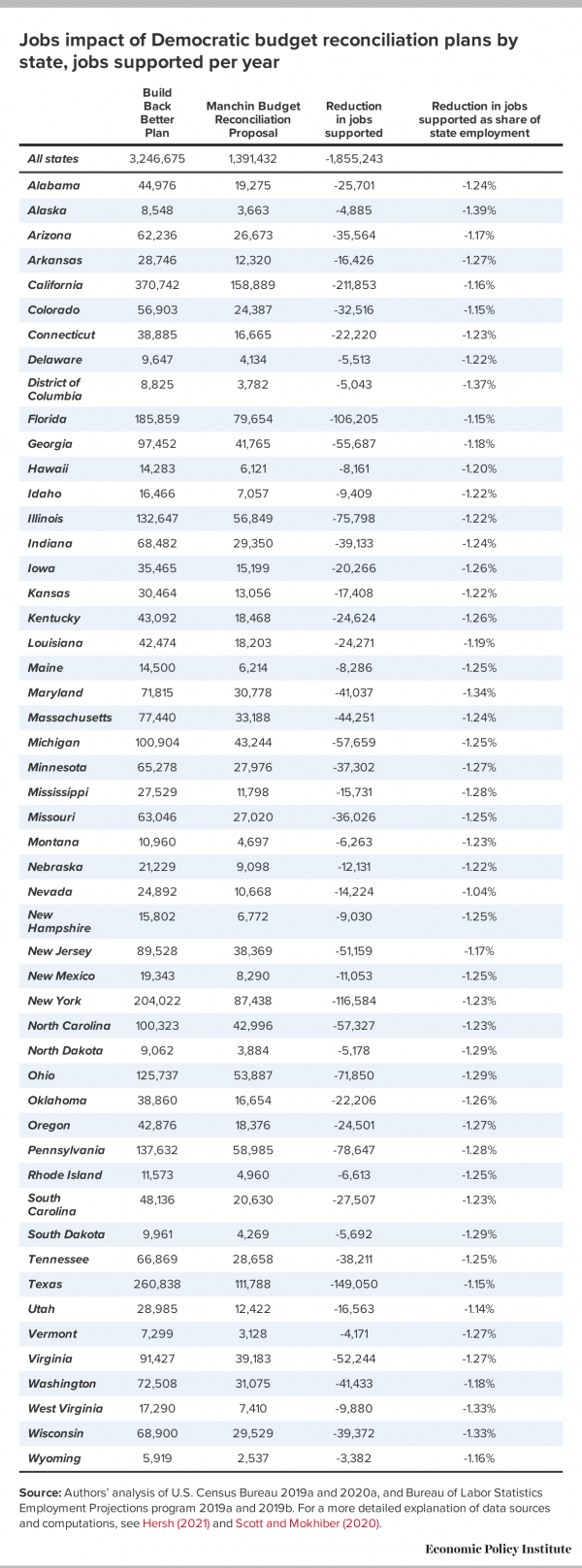

How much will such compromise cost the U.S. economy? We crunched the numbers to find out what compromising on the BBB plan will mean for every state and congressional district in the United States. If the budget reconciliation package is cut from $3.5 trillion to $1.5 trillion—as Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) has called for—nearly 2 million fewer jobs per year would be supported.

In a previous analysis, we showed that the BBB agenda—combining the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework and the proposed $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation package—would support more than 4 million jobs annually. It would also make critical investments that would deliver relief to financially strained households, raise productivity, and dampen inflation pressures to enhance America's long-term economic growth prospects. David Brooks, the center-right New York Times columnist, recently captured the significance of these initiatives when he wrote that these are "economic packages that serve moral and cultural purposes. They should be measured by their cultural impact, not merely by some wonky analysis. In real, tangible ways, they would redistribute dignity back downward."

Senators Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) are intent on scaling back Build Back Better's purpose. While Sen. Sinema has not publicly staked a position outlining her objections, Sen. Manchin has telegraphed a top-line spending figure of $1.5 trillion as the maximum he would support.

The $2 trillion gap left by Manchin's proposal cuts far deeper than any of the policy specifics he proposes eliminating. Even if he succeeded in eliminating all climate-related funding in the BBB agenda budget resolution, for example, Manchin's plan would still fall nearly $1.8 trillion short. Thus, for the purpose of our analysis, it makes most sense to assume that hewing to Sen. Manchin's demands would mean a proportional cut across all of the BBB agenda's individual initiatives (more on the methodologies used here and here).

Besides delivering fewer tangible benefits to typical families, scaling back Build Back Better also severely compromises the package's value as macroeconomic insurance against recovery waning in the coming years.

Absent the Build Back Better package, there is no guarantee of robust growth once the provisions of the American Rescue Plan—enacted in March of this year—begin fading out in earnest in mid-2022. The U.S. economy is not out of the woods yet. In past instances, policymakers have too often erred on the side of withdrawing fiscal support too early, resulting in protracted recoveries and prolonged spells of elevated unemployment, which ultimately undercut America's future economic potential. The BBB package would counter a potential slump and effectively support millions of jobs, especially if a host of plausible scenarios occur, including:

- if private spending fails to sustain growth after the American Rescue Plan fades;

- if the pandemic evolves and continues weighing on economic activity;

- or if other unforeseen shocks to the economy emerge and threaten a robust recovery.

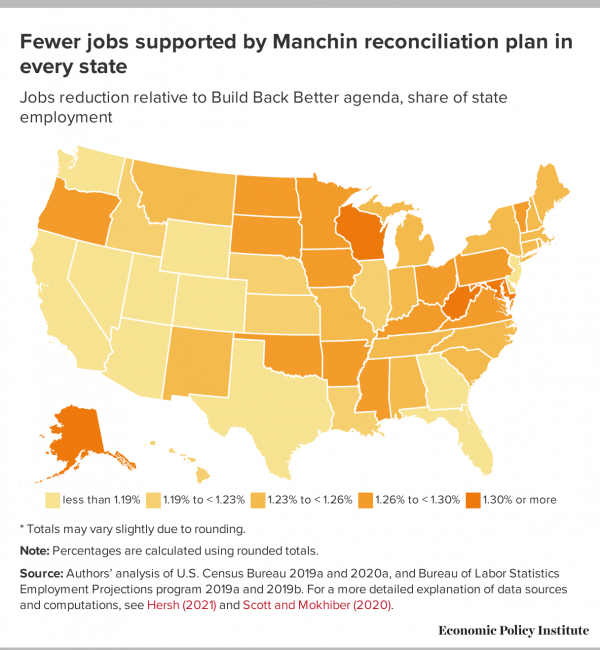

Scaling back the plan now, as Sens. Manchin and Sinema would like, will support millions fewer than the original package. In total, Sen. Manchin's proposal would support nearly 1.9 million fewer jobs per year than the Build Back Better agenda. Full results for each state and congressional district can be downloaded here and in the figures and table below.

- Every state and Washington, D.C. would see fewer jobs supported under Sen. Manchin's proposal than the BBB agenda. The largest states would experience the largest absolute losses in jobs potential. California would see 211,853 fewer jobs per year, while Texas, New York, and Florida would see 149,050, 116,584, and 106,205 fewer jobs per year, respectively.

- West Virginia would see 9,880 fewer jobs annually under Manchin's plan, equivalent to 1.33% of the state's overall employment. West Virginia would be no better off in terms of jobs in fossil fuel industries, but would see 900 fewer manufacturing jobs, 400 fewer construction jobs, and 3,800 fewer health care and social assistance jobs.

- Arizona would see 35,564 fewer jobs per year, equal to 1.17% of state employment, including 2,500 fewer manufacturing jobs, 1,600 fewer construction jobs, and 11,400 fewer health care and social assistance jobs.

- Alaska would be most impacted by fewer jobs under Manchin's proposal relative to the size of its economy, losing out on jobs equivalent to 1.39% of its total employment, but all states and DC would forego more than 1% of total employment.

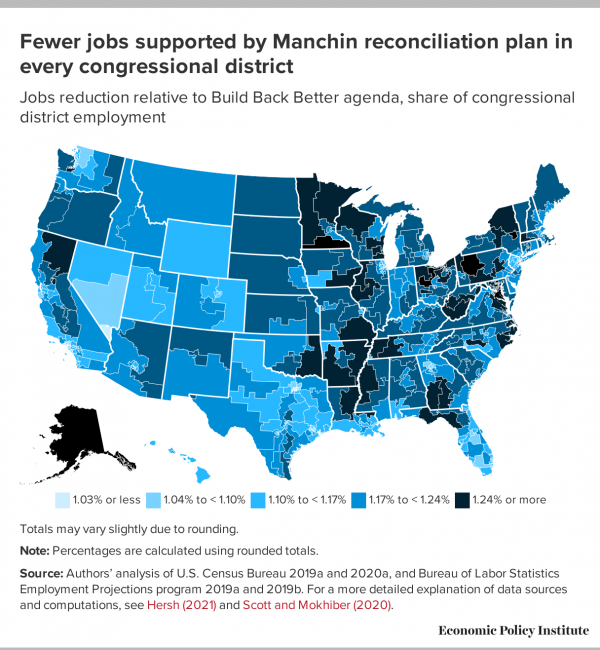

- All congressional districts will see fewer jobs supported under Manchin's proposal than under the BBB plan, ranging from 0.9 to 1.5% fewer jobs supported as a share of overall district-level employment.

- Districts represented by so-called moderate House Democrats would take material hits to jobs under Manchin's plan relative to the BBB reconciliation plan. Rep. Josh Gottheimer's (D-NJ 5th) would see support for 7,700 fewer jobs per year in his district under Manchin's proposal and Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-FL 7th) would see 7,600 fewer jobs. Altogether, the bloc of 10 moderate Democratic members would see 70,700 fewer jobs supported across their districts relative to the BBB plan.

- Manchin and Sinema have become linchpins in this legislative negotiation to a large extent because of an ideological hollowing out of the "center" of Republican party officials. Supposedly moderate Senate Republicans would not even entertain engagement over the broader Biden-Harris economic agenda, but their constituencies, too, would be worse off under Sen. Manchin's proposal to cut the BBB agenda.

- Maine would see 8,300 fewer jobs supported per year, or 1.3% of state employment.

- Utah would see 16,600 fewer jobs per year.

- Ohio would miss out on economic support for an additional 71,900 jobs annually.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Sunday, October 10, 2021

Dean Baker Deep dive on the Jobs Report and Supply chain issues

If President Biden was designing a jobs report to advance his Build Back Better agenda, he could not have done better than the September jobs report. (No, he didn't manipulate the data.) It shows the need for improving our caring infrastructure to make it possible for more women to work. It also shows the need to improve our infrastructure to limit supply chain disruptions.

But before getting to these issues, it's first important to dispel the idea that this was a bad jobs report. The September data showed a 0.4 percentage point drop in the unemployment rate, bringing it to 4.8 percent. Most analysts had predicted a drop of just 0.1 or 0.2 percentage points. We didn't get the unemployment rate down to 4.8 percent following the Great Recession until January of 2016. And, this decline was due to workers getting jobs, not the unemployed dropping out of the labor market. The number of employed in the household survey increased by 526,000.

The negative view of the September report is based on the weaker than expected job growth reported in the establishment survey. The increase of 194,000 in payroll jobs was well below the 400,000 to 500,000 job gain most analysts had expected. While that seems like a bad story, a closer look shows otherwise.

The biggest contributor to the weak job growth story was the loss of 161,000 jobs in state and local government education. There is not an obvious explanation for this job loss (I'll come to back to this issue), but suppose that we didn't see this sort of job loss in public sector education. Suppose that we instead regained more of the education jobs lost in the pandemic.

The private sector added a healthy 317,000 jobs in September. If the public sector had added 100,000 jobs for the month, as many had expected, the Bureau of Labor Statistics would have reported job growth of 417,000 in September, well within the generally expected range.

So, the big question is why are we losing jobs in education instead of adding them? It's hard to come up with a good story here. Some analysts have suggested the problem is with the seasonal adjustment. On an unadjusted basis, state and local education added 1,033,000 jobs in September. The argument is that the seasonal adjustment is inappropriate for this year, since the pandemic has altered the normal timing of the school year and employment patterns.

But this argument really doesn't fit. If we just look at the non-seasonally adjusted data, employment in public education is down 431,000 from the levels of September of 2019, a decline of 4.8 percent. Schools are back to in-class instruction pretty much everywhere. Unless we have seen a sharp rise in student-to- teacher ratios, or a large decline in support staff, this drop in employment from before the pandemic doesn't make sense.

Anyhow, we will need to sort out what is going on with employment in public schools, but if we set that issue aside for the moment, the jobs picture in the establishment survey looks pretty good. As noted earlier, the 317,000 private sector jobs added in the month was very much consistent with expectations. But an element of the picture that has not gotten nearly attention it deserves is the increase in the length of the average workweek.

The average workweek rose by 0.2 hours. This rise in average weekly hours, coupled with the rise in employment, led to a rise of 0.9 in the index of aggregate hours. This is the largest increase since March.

A story that is consistent with a rise in hours, coupled with a limited increase in payroll employment, is that employers are having trouble getting the workers they need to meet the demand they are seeing. They adjust to this situation by working their existing workforce more hours.

The continued rapid growth in wages, especially for lower paid workers, fits with this supply-side story. The average hourly for production and non-supervisory workers increased at a 6.7 percent annual rate comparing last 3 months (July August, September) with the prior 3 months (April, May, June). In the leisure and hospitality sector (primarily restaurants) the annual rate of wage growth over this period has been 18.1 percent.

The implication of this view is that the limitation on employment growth at this point is largely a supply story, not a lack of demand. Workers are not returning to low-paying jobs, at least not without getting considerably higher pay and/or an improvement in working conditions.

The sectors showing the largest percentage drop in employment from pre-pandemic levels are overwhelmingly low-paying. Employment in nursing homes is down 15.2 percent.Employment in child care is down by 10.4 percent from its pre-pandemic level. Employment in the temporary help sector is down 8.7 percent. Restaurant employment is down by 7.6 percent from its pre-pandemic level. By comparison, overall employment in the private sector is down by just 3.0 percent.

It is worth noting here that the $300 weekly unemployment insurance supplements, and the special pandemic unemployment insurance programs, are not likely a big factor in discouraging people from working. Most states ended the supplements and pandemic programs in June and July. The national program ended in early September. If these benefits were discouraging people from working, we should have seen most of the effect from ending them by September.

Increasing Labor Force Participation

While we are going to see some reshuffling of the workforce, which will take time to work through, we can easily identify the reason some people, specifically women, are not working or looking for work. The BLS reported that 1.6 million people, 960,000 of them women, were not working or looking for work because of the pandemic.

This is presumably because they either fear getting Covid themselves or transmitting it to a family member who may have a health condition, or may be caring for a family member who is already ill. If these 1.6 million people were in the labor force, it would reduce by more than one third the falloff in labor force participation since the start of the pandemic. This again shows the economic importance of Biden's efforts to control the pandemic.

Of course, the issue of women's labor force participation long predates the pandemic. While the United States was near the top among wealthy countries in women's labor force participation four decades ago, it is now a laggard. It not only ranks below the Nordic countries, it has also been passed by France, Germany and even Japan in women's labor force participation.

According to the OECD, in 1980 the labor force participation rate (LFPR) for prime age women (ages 25 to 54) was 64.0 percent in the United States. That was slightly lower than the 64.7 percent rate for France, but well above the 56.7 percent rate for Japan and 56.6 percent rate for Germany. In 2020, the LFPR for prime age women in the United States had increased to 75.1 percent, but it had risen to 82.6 percent in France, 84.5 percent in Germany, and 80.0 percent in Japan.

The reason the U.S. is a laggard is not a secret. We lag in providing access to child care and family leave. Since woman continue to disproportionately have caregiving responsibilities for children and family members in need of assistance, our failure in these areas makes it difficult for many women to work.

This is a problem that has gotten worse in the pandemic. As noted earlier, employment in child care in September was 10.4 percent below its pre-pandemic level. Since there has not likely been a boom in productivity in this sector, this drop in employment means that the number of child care slots is likely close to 10.0 percent lower than before the pandemic. That means that finding quality child care is even more difficult today than it was a year and a half ago.

Getting more child care workers means raising the pay and improving conditions for child care workers. This is one of the key provisions of Building Back Better plan. Improved access to child care, along with paid parental leave (another provision) will give millions of women the option of working.

These provisions are also likely to lead to better outcomes for children in terms of education and employment, which is both good for them and good for the economy in the long-run. But, by increasing access to child care and providing parental leave, we can see a near-term boost to the economy from more people working. If getting more people working is a goal of our economic policy, this is an important route for getting there.

Supply Chain Problems

The September jobs report also gave us a reminder about the country's supply chain problems. The number of people employed in automobile manufacturing fell by 6,100. This is undoubtedly due to the widely publicized shortage of semiconductors, which is result of a fire at a major manufacturing facility in Japan. There surely are other industries where supply disruptions limited employment, although the link may be less clear than in the auto industry.

There are several points worth making here. First, in the context of a worldwide pandemic, our supply chains have actually held up remarkably well. At least in the United States, we have not had problems of people not getting food, medicine, and other necessities. Given the size of the shock, having to wait an extra month or two for a car, or paying five percent more, hardly sees like a great tragedy. Still, we don't want to see these delays and the resulting economic slowdown if it can be avoided.

It is important to note that the takeaway from the shortages is that we need diverse sources of supply, which does not necessarily mean domestic sources. If we rely on a manufacturer in Malaysia for a product, which then become unavailable for whatever reason, if we can get the product from Korea or Mexico, that is fine. There is no special virtue on this issue in getting it from the United States.

This matters because we can see shutdowns by U.S. producers as well. Marketplace radio had a piecelast month about a shortage of paint across the country. According to the piece, one of the main culprits was a shutdown by resin manufacturers (an ingredient in paint) in Texas last winter due to the unusually cold weather. In this case, relying on domestic suppliers did not prevent a supply chain disruption.

Another key point is that much of the problem is not actually in producing the items, but in transporting them. The Washington Post had an excellent piecethat described the backlog in our ports and on railways that is preventing items from getting to their destination. This means that even if we are getting the goods from China, Thailand, or anywhere else, they are not getting to where they need to go because of inadequate infrastructure. Modernizing our ports and railways is another key part of Biden's Building Back Better plan.

Global Warming and Supply Chain Disruptions

The last area where the September job report is an advertisement for the Build Back Better plan is on climate change. Many of the supply chain disruptions we are seeing now, and will see in the future, are the result of global warming.

The cold Texas weather, that led to the shutdown of the resin manufacturers, which contributed to the paint shortage, was an extraordinary weather event that likely would not have occurred if we were not experiencing climate change. More frequent hurricanes and other extreme weather events, that lead to shutdowns in manufacturing or distribution facilities, will be more common as global warming advances. And, we will see more crop failures and higher prices for a wide range of agricultural products due to excessive heat and droughts.

If we don't begin to make serious efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as proposed in the Build Back Better plan, we will see many more climate related economic disruptions in future years, as well as higher prices for a wide range of products.

Conclusion: The September Jobs Report Was an Advertisement for Build Back Better

There are many aspects to the jobs report that gave ambiguous signals about the near-term future for the economy. However, the problems that are most apparent in this report indicate the urgency of many of the items in Biden's agenda. Our senators and congresspeople should give them serious thought.

‘It’s Not Sustainable.’ What America’s Port Crisis Looks Like Up Close. [feedly]

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/10/business/supply-chain-crisis-savannah-port.html

-- via my feedly newsfeed

y Peter S. GoodmanPhotographs by Erin Schaff

Oct. 10, 2021, 11:35 a.m. ET

SAVANNAH, Ga. — Like toy blocks hurled from the heavens, nearly 80,000 shipping containers are stacked in various configurations at the Port of Savannah — 50 percent more than usual.

The steel boxes are waiting for ships to carry them to their final destination, or for trucks to haul them to warehouses that are themselves stuffed to the rafters. Some 700 containers have been left at the port, on the banks of the Savannah River, by their owners for a month or more.

"They're not coming to get their freight," complained Griff Lynch the executive director of the Georgia Ports Authority. "We've never had the yard as full as this."

As he speaks, another vessel glides silently toward an open berth — the 1,207-foot-long Yang Ming Witness, its decks jammed with containers full of clothing, shoes, electronics and other stuff made in factories in Asia. Towering cranes soon pluck the thousands of boxes off the ship — more cargo that must be stashed somewhere.

"Certainly," Mr. Lynch said, "the stress level has never been higher."

It has come to this in the Great Supply Chain Disruption: They are running out of places to put things at one of the largest ports in the United States. As major ports contend with a staggering pileup of cargo, what once seemed like a temporary phenomenon — a traffic jam that would eventually dissipate — is increasingly viewed as a new reality that could require a substantial refashioning of the world's shipping infrastructure.

As the Savannah port works through the backlog, Mr. Lynch has reluctantly forced ships to wait at sea for more than nine days. On a recent afternoon, more than 20 ships were stuck in the queue, anchored up to 17 miles off the coast in the Atlantic.

Image

Nearly 80,000 containers jam the the port, 50 percent more than usual.

Such lines have become common around the globe, from the more than 50 ships marooned last week in the Pacific near Los Angeles to smaller numbers bobbing off terminals in the New York area, to hundreds waylaid off ports in China.

The turmoil in the shipping industry and the broader crisis in supply chains is showing no signs of relenting. It stands as a gnawing source of worry throughout the global economy, challenging once-hopeful assumptions of a vigorous return to growth as vaccines limit the spread of the pandemic.

The disruption helps explain why Germany's industrial fortunes are sagging, why inflation has become a cause for concern among central bankers, and why American manufacturers are now waiting a record 92 days on average to assemble the parts and raw materials they need to make their goods, according to the Institute of Supply Management.

On the surface, the upheaval appears to be a series of intertwined product shortages. Because shipping containers are in short supply in China, factories that depend on Chinese-made parts and chemicals in the rest of the world have had to limit production.

Daily business updates The latest coverage of business, markets and the economy, sent by email each weekday. Get it sent to your inbox.

But the situation at the port of Savannah attests to a more complicated and insidious series of overlapping problems. It is not merely that goods are scarce. It is that products are stuck in the wrong places, and separated from where they are supposed to be by stubborn and constantly shifting barriers.

The shortage of finished goods at retailers represents the flip side of the containers stacked on ships marooned at sea and massed on the riverbanks. The pileup in warehouses is itself a reflection of shortages of truck drivers needed to carry goods to their next destinations.

For Mr. Lynch, the man in charge in Savannah, frustrations are enhanced by a sense of powerlessness in the face of circumstances beyond his control. Whatever he does to manage his docks alongside the murky Savannah River, he cannot tame the bedlam playing out on the highways, at the warehouses, at ports across the ocean and in factory towns around the world.

"The supply chain is overwhelmed and inundated," Mr. Lynch said. "It's not sustainable at this point. Everything is out of whack."

Born and raised in Queens with the no-nonsense demeanor to prove it, Mr. Lynch, 55, has spent his professional life tending to the logistical complexities of sea cargo. ("I actually wanted to be a tugboat captain," he said. "There was only one problem. I get seasick.")

Now, he is contending with a storm whose intensity and contours are unparalleled, a tempest that has effectively extended the breadth of oceans and added risk to sea journeys.

Last month, his yard held 4,500 containers that had been stuck on the docks for at least three weeks. "That's bordering on ridiculous," he said.

"Everything is out of whack," said Griff Lynch, the executive director of the Georgia Ports Authority.

That these tensions are playing out even in Savannah attests to the magnitude of the disarray. The third-largest container port in the United States after Los Angeles-Long Beach and New York-New Jersey, Savannah boasts nine berths for container ships and abundant land for expansion.

B

To relieve the congestion, Mr. Lynch is overseeing a $600 million expansion. He is swapping out one berth for a bigger one to accommodate the largest container ships. He is extending the storage yard across another 80 acres, adding room for 6,000 more containers. He is enlarging his rail yard to 18 tracks from five to allow more trains to pull in, building out an alternative to trucking.

But even as Mr. Lynch sees development as imperative, he knows that expanded facilities alone will not solve his problems.

"If there's no space out here," he said, looking out at the stacks of containers, "it doesn't matter if I have 50 berths."

Many of the containers are piled five high, making it harder for cranes to sort through the towers to lift the needed boxes when trucks arrive to take them away.

Image

The port has nine berths for container ships and abundant land for expansion.

Image

Containers are filled with everything from tires to holiday decorations.

Image

Nearly 13 percent of the world's cargo shipping capacity is tied up by delays, data shows.

On this afternoon, under a merciless sun, the port is on track to break its record for activity in a single day — more than 15,000 trucks coming and going. Still, the pressure builds. A tugboat escorts another ship to the dock — the MSC AGADIR, fresh from the Panama Canal — bearing more cargo that must be parked somewhere.

In recent weeks, the shutdown of a giant container terminal off the Chinese city of Ningbo has added to delays. Vietnam, a hub for the apparel industry, was locked down for several months in the face of a harrowing outbreak of Covid. Diminished cargo leaving Asia should provide respite to clogged ports in the United States, but Mr. Lynch dismisses that line.

"Six or seven weeks later, the ships come in all at once," Mr. Lynch said. "That doesn't help."

Early this year, as shipping prices spiked and containers became scarce, the trouble was widely viewed as the momentary result of pandemic lockdowns. With schools and offices shut, Americans were stocking up on home office gear and equipment for basement gyms, drawing heavily on factories in Asia. Once life reopened, global shipping was supposed to return to normal.

Image

The port is undergoing a $600 million expansion to relieve the congestion.

But half a year later, the congestion is worse, with nearly 13 percent of the world's cargo shipping capacity tied up by delays, according to data compiled by Sea-Intelligence, an industry research firm in Denmark.

Many businesses now assume that the pandemic has fundamentally altered commercial life in permanent ways. Those who might never have shopped for groceries or clothing online — especially older people — have gotten a taste of the convenience, forced to adjust to a lethal virus. Many are likely to retain the habit, maintaining pressure on the supply chain.

"Before the pandemic, could we have imagined mom and dad pointing and clicking to buy a piece of furniture?" said Ruel Joyner, owner of 24E Design Co., a boutique furniture outlet that occupies a brick storefront in Savannah's graceful historic district. His online sales have tripled over the past year.

On top of those changes in behavior, the supply chain disruption has imposed new frictions.

Image

The port is enlarging the rail yard to 18 tracks from five to allow more trains to pull in, giving shippers an alternative to trucking.

Mr. Joyner, 46, designs his furniture in Savannah while relying on factories from China and India to manufacture many of his wares. The upheaval on the seas has slowed deliveries, limiting his sales.

He pointed to a brown leather recliner made for him in Dallas. The factory is struggling to secure the reclining mechanism from its supplier in China.

"Where we were getting stuff in 30 days, they are now telling us six months," Mr. Joyner said. Customers are calling to complain.

His experience also underscores how the shortages and delays have become a source of concern about fair competition. Giant retailers like Target and Home Depot have responded by stockpiling goods in warehouses and, in some cases, chartering their own ships. These options are not available to the average small business.

Bottlenecks have a way of causing more bottlenecks. As many companies have ordered extra and earlier, especially as they prepare for the all-consuming holiday season, warehouses have become jammed. So containers have piled up at the Port of Savannah.

Mr. Lynch's team — normally focused on its own facilities — has devoted time to scouring unused warehouse spaces inland, seeking to provide customers with alternative channels for their cargo.

Recently, a major retailer completely filled its 3 million square feet of local warehouse space. With its containers piling up in the yard, port staff worked to ship the cargo by rail to Charlotte, N.C., where the retailer had more space.

Such creativity may provide a modicum of relief, but the demands on the port are only intensifying.

On a muggy afternoon in late September, Christmas suddenly felt close at hand. The containers stacked on the riverbanks were surely full of holiday decorations, baking sheets, gifts and other material for the greatest wave of consumption on earth.

Will they get to stores in time?

"That's the question everyone is asking," Mr. Lynch said. "I think that's a very tough question."

Image

Friday, October 8, 2021

Enlighten Radio:Talkin Socialism: The Challenge of Big Tech

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Talkin Socialism: The Challenge of Big Tech

Link: https://www.enlightenradio.org/p/talkin-socialism-challenge-of-big-tech.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/