Overview

Implementing policies that improve job quality in the United States could come with a direct cost, such as the cost to a U.S. company from raising wages or providing more paid time off. For these reasons, business interests often argue against policies that improve U.S. labor standards. Yet these qualms are short-sighted. Research on the cost of employee turnover reveals that it costs an average of 40 percent of an individual employee's annual salary to find a replacement if that employee leaves in search of better job opportunities.

In contrast, U.S. labor market policies that improve job quality have been shown to increase job tenure. Reducing the cost of employee turnover and improving the well-being of workers reinforce each other to the benefit of both companies and workers.

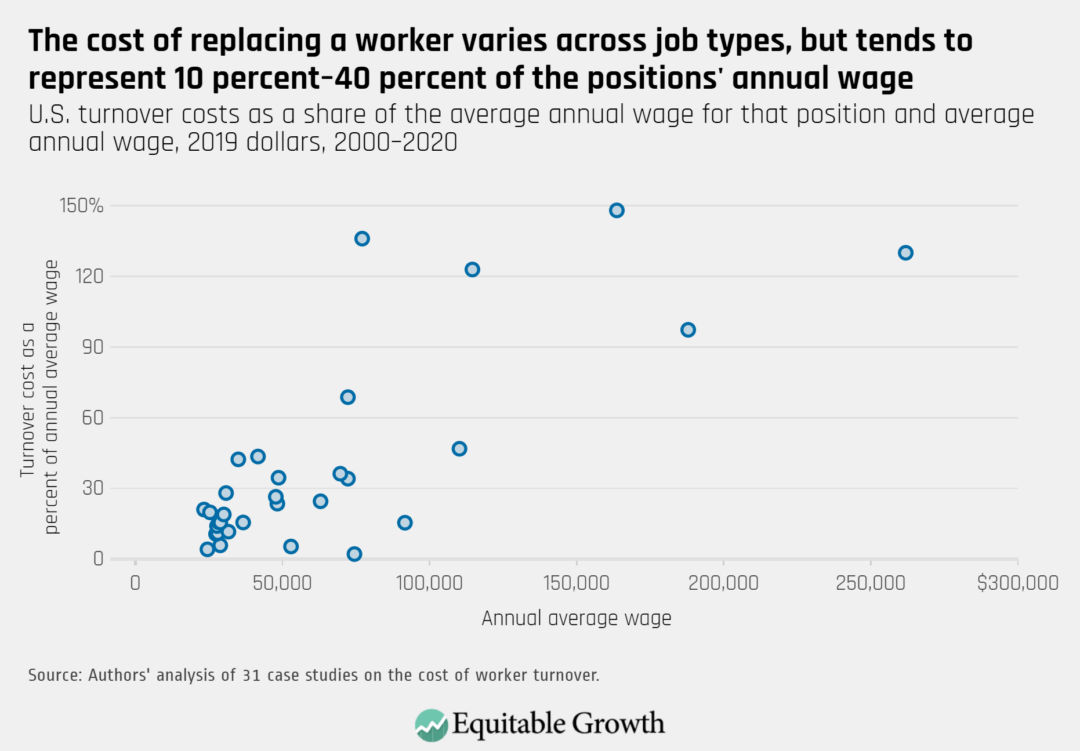

This issue brief reviews the economic literature on the cost of employee turnover. We present the evidence that there is a dollar value to replace a worker and get the next hire up to speed, which could be deferred by keeping those workers in their jobs if it is an otherwise good fit for their skills and passions. The costs of turnover range from 2 percent to almost 150 percent and vary across industries, but the sum of this research demonstrates the case for providing better jobs in the first place.

The research on employee turnover also points us to the solutions. Raising the floor on job quality sorts workers into jobs for which they are best matched. And employers are less likely to risk losing good workers when they search for the benefits needed to improve their well-being. These policy solutions include increasing earnings with policy tools such as minimum wages, giving workers a voice in their workplaces, and enforcing anti-discrimination protections so that no worker feels stuck between a hostile workplace and unemployment.

How employee turnover costs U.S. businesses revenues and profits

For businesses, the cost of losing and replacing a worker goes well beyond the cost of a new hire. These costs can amount to big financial losses. Because jobs in high-turnover industries and occupations are associated with low wages and lack of access to employer-provided benefits, the rate at which employees leave and are replaced has important implications for both workers and employers. Yet many businesses do not know or underestimate the toll that high turnover has on their workforce, their sales, and their bottom lines.

Studies that estimate the cost of losing and replacing a worker generally takes into account direct expenses such as the resources that go into advertising an open position, interviewing and screening candidates, and onboarding a recently hired worker. Consider the analysis of Iowa's direct care professionals—home health aides, nurse assistants, and patient care technicians—that shows paying overtime to make up for the loss of capacity while a position is vacant, recruiting, and training a new hire amounted to $4,026 per worker in 2013. Because these positions tend to pay low wages, provide few benefits, and expose workers to injuries, that year's high turnover is estimated to have cost service-providing companies in Iowa almost $200 million in direct expenses alone.

And turnover also has indirect, less-easy-to-observe costs. A study analyzing the U.S. supermarket industry finds that when accounting for opportunity or indirect costs of an employee leaving (such as paperwork errors or the loss of customers due to a decline in the quality of service), per-employee turnover costs more than doubled. For instance, the direct replacement costs of a nonunion supermarket cashier averaged $736 in 2000, but this number jumped to $1,550 when factoring in indirect costs. As such, estimates can vary widely not only because expenses are different across sectors and job types, but also because academic researchers and employers use a wide range of inputs to arrive at a dollar value of losing and replacing a worker. As a result, calculations tend to represent a conservative estimate of the true cost of turnover.

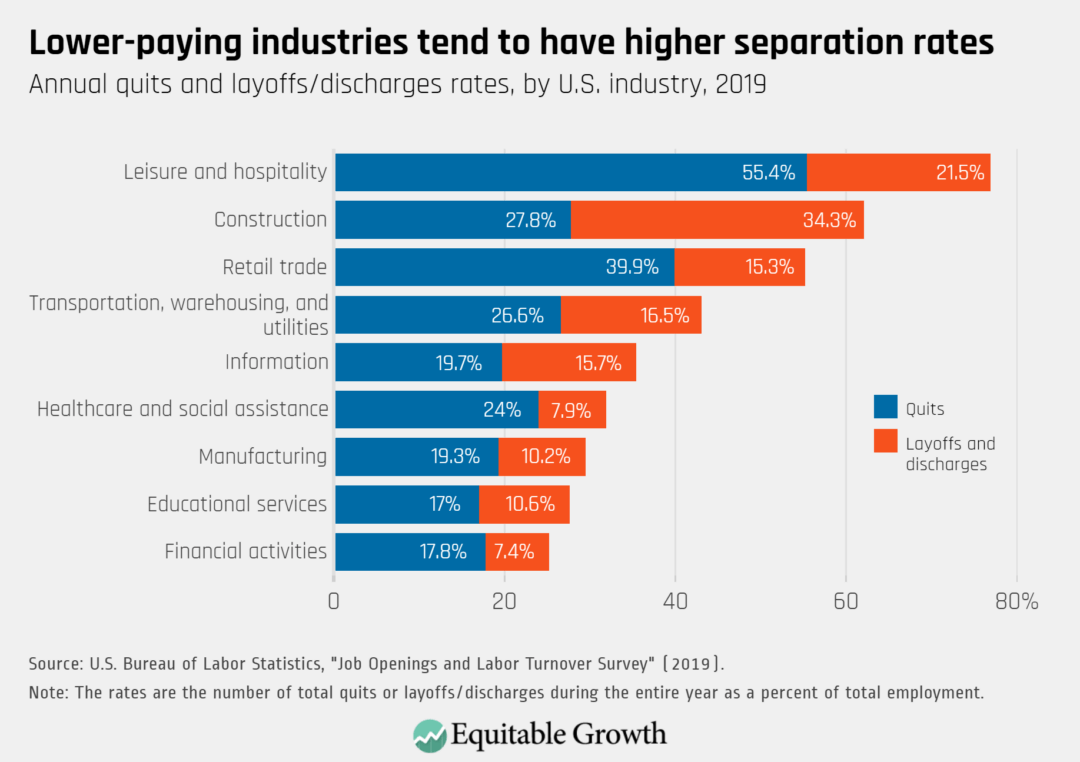

That being said, high turnover is more prevalent in some industries than others. The rates of quits and layoffs—the total number of quits and layoffs in a given period of time as a share of total employment—are highest in leisure and hospitality, construction, and retail. That workers in service industries such as retail and leisure and hospitality are particularly likely to voluntarily leave their jobs is, in no small part, a function of low pay (these two sectors have the lowest average wages among the major U.S. industries), lack of access to employer-provided benefits, and management practices that chip away at workers' sense of well-being and job security, such as unpredictable work schedules. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

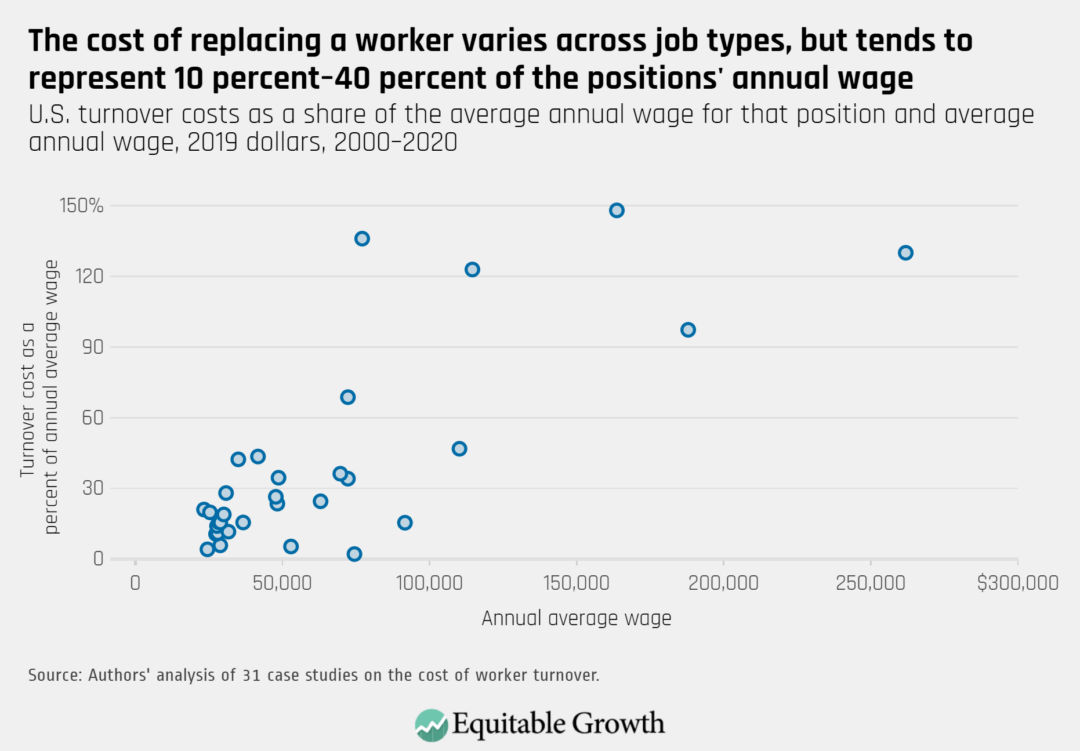

In this issue brief, we analyze 37 case studies in 14 research articles published between 2000 and 2020 (see Table 1 in the Methodological Appendix for a summary of the studies and calculations for each position). The main estimates pool 31 case studies in order to calculate turnover costs as a percent of a given position's average annual wage, and include jobs in the healthcare, education, hospitality, finance, retail, transportation, and manufacturing industries. The results are the following:

- On average, turnover costs represent 39.6 percent of a position's annual wage. Across the 31 case studies included in our estimates, the median cost of turnover represented 23.5 percent of a worker's annual wage.

- For workers earning less than the 2019 average annual wage ($53,490), turnover costs made up 19.3 percent of their annual wage.

- In the two major sectors for which at least five case studies are available, turnover costs as a share of average annual wage are as follows: health services (32.7 percent) and hospitality (19.6 percent).

Emblematic of these findings are the overall costs of replacing a worker across industries up and down the U.S. wage ladder in the 21st century. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Reduce employee turnover by increasing U.S. job quality

One of the most basic ways reduce turnover and increase job tenure is to improve job quality by increasing earnings. In the United States, the minimum wage is the strongest tool to do this. Like other labor policies, opponents of the minimum wage argue that it imposes too high of a cost on businesses, which will respond by reducing employment levels. Yet the breadth of high-quality research on the minimum wage demonstrates that increasing the statutory minimum wage did not reduce employment and increased worker tenure. Across low-wage work and within critical industries such as nursing homes, increasing wages has positive effects for workers and the provision of services, with minimal costs to businesses.

In an Equitable Growth working paper by Kevin Rinz and John Voorheis of the U.S. Census Bureau, the authors use administrative data to follow workers who, over time, were affected by a minimum wage increase in their local labor market. They find that workers in affected jobs experienced wage increases and did not lose employment, which ultimately leads to longer job tenure and increased earnings growth at the lower end of the income distribution. These findings are reinforced by the broad trend of estimating the impact of the minimum wage with administrative data and increasing the accuracy of findings. These estimates show that long-term earnings are increased without reducing employment levels.

The studies reviewed in this issue brief are across a wide variety of occupations, industries, and income levels, many of which would not be directly impacted by a minimum wage increase. But this does not mean statutory wage levels cannot be instituted across earnings levels to improve job quality and increase worker tenure. In Equitable Growth's Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, an essay by Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts Amherst develops a proposal for establishing wage standards by industry and occupation so that workers are able to receive earnings aligned with the value they create.

Reduce employee turnover by improving U.S. labor standards

Another metric of job quality is worker voice in their jobs, which, in the United States, is primarily achieved by unionization. In a paper on the impact of unions on job satisfaction and turnover, Trove Hammer and Ariel Avgar of Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations find that unionized workers are more likely to remain in their jobs, yet this may reduce some job satisfaction. A study by Steven Abraham and Barry Friedman of the State University of New York at Oswego and Randall Thomas of Ipsos, formerly of Harris Interactive, surveys workers by union status on job satisfaction and intent to leave a job. They find that job dissatisfaction is more strongly correlated with intent to leave for nonunion members, compared to union members.

Union membership subdues the impact of other variables associated with intent to leave a job, increasing the job tenure of unionized workers. A body of research examines why unions may increase job dissatisfaction while still increasing tenure. One theory is that greater information is available to unionized workers, inducing what Richard Freeman and James Medoff called "voice-induced complaining" in their seminal text, "What Do Unions Do?". A very recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper by David Blanchflower of Dartmouth College and Alex Bryson of University College London finds that the relationship between union membership and job satisfaction has become positive. Using data from the Gallup U.S. Daily Tracker Poll from 2009 to 2013, they find that unions had a positive effect on job satisfaction in the years following the Great Recession, as the protective effect of unions increased job security among members.

Reducing employee turnover is particularly important to public-sector work, where unions are also more prevalent and where recent attrition in the public-sector workforces is a particular cause for concern. Emma García and Elaine Weiss of the Economic Policy Institute find that there is a shortage of teachers in the Kindergarten through 12th grade education system that has increased in recent years. In a study on unionized teachers in New York state, Yujin Choi of Ewha Womans University and Il Hwan Chung of Soongsil University find a positive relationship between the strength of grievance procedures and a lower likelihood of turnover. And a report by Rich Jones of the Economic Analysis Research Network on Colorado finds that turnover in the public sector has increased in the state over the past 10 years—a phenomenon that could be offset by increasing collective bargaining, which would ultimately improve the provision of public services.

Efforts to increase the coverage of collective bargaining agreements in the United States include proposals in Harvard University's Labor and Worklife Program's "clean slate for worker power" agenda that could pave the way to increase unionization and, by association, reduce worker turnover.

In addition to increasing worker voice at their jobs through unionization, worker involvement in workplace decision-making may broadly reduce turnover. In a study with administrative data from Denmark, Elena Cottini of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Takao Kato of Colgate University, and Niels Westergård-Nielsen of Copenhagen Business School find that "high-involvement work practices," where human resources policies allow for workers to produce knowledge in a systematic way and have a say in workplace practices, reduce worker turnover.

Worker involvement in establishment decision-making can also be bolstered through policies such as co-determination, where worker representatives have a seat on corporate boards. In a recent study by Equitable Growth grantees Simon Jäger of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Benjamin Schoefer of the University of California, Berkeley, along with Jörg Heining of the German Institute for Employment Research, co-determination is not associated with higher wages at firms with workers on boards, but also does not negatively impact firm's bottom line.

Hostile workplaces are also more likely to experience employee turnover, particularly given currently poorly enforced labor laws such as anti-discrimination protections, which give workers little recourse other than to leave their jobs and potentially suffer long-term earnings consequences. Research on sexual harassment in the workplace finds that it increases employee turnover, which, in turn, constitutes the greatest cost of sexual harassment for companies—more than litigation costs.

Likewise, lack of representation across race and ethnicity can result in burnout from the few workers from underrepresented groups in a workplace. This dynamic is detailed in Adia Harvey-Wingfield's recent book Flatlining: Race, Work, and Health Care in the New Economy. Then, there is racial discrimination in healthcare workplaces, which is shown to increase employee turnover. Well-enforced anti-discrimination protections, where workers have recourse without fear of retaliation, and workplace inclusion would both create higher-quality jobs for workers of color and women workers.

Conclusion

Improving U.S. labor standards to protect workers from discrimination in the workplace and to boost earnings and workers' voices on the job would benefit their employers by reducing the costs of employee turnover. This issue brief documents that businesses prioritizing low labor costs over job quality are misguided because they do not take into consideration the significant costs of replacing a worker. The research reviewed in this issue brief finds that the cost of turnover is an average of 40 percent of a worker's salary. To avoid these significant costs, workplaces that provide higher-quality jobs, particularly those with decent pay and a voice at work, have lower turnover and longer employee tenure.

Policies to increase earnings through higher minimum wages and wage boards would take a first step in helping companies avoid losing workers. Expanding unionization would go a long way to increasing worker tenure as well. Workers also need to be protected from discrimination and harassment at work, so that they are not left to choose between job security and their own well-being, which often results in them choosing to leave jobs at a cost to both themselves and the company.

Improving the enforcement of U.S. anti-discrimination protections would give workers recourse within their jobs, potentially reducing turnover and limiting costs to the company at the same time. Improving job quality will increase the well-being of workers, who will then be more likely to stay at a job, thus increasing their firm-specific human capital and productivity in a virtuous cycle where workers are able to share in the gains of economic growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed