China Thinks America Is Losing

Washington Must Show Beijing It's Wrong

The consequences of the presidency of Donald Trump will be debated for decades to come—but for the Chinese leadership, its meaning is already clear. China's rulers believe that the past four years have shown that the United States is rapidly declining and that this deterioration has caused Washington to frantically try to suppress China's rise. Trump's trade war, technology bans, and determination to blame China for his own mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic have all confirmed the perception of Chinese policy elites that the United States is bent on keeping their country down.

To be sure, the idea that the United States seeks to stymie and contain China was widespread among Chinese officials long before Trump came to power. What many Americans see as disruptive effects attributable only to Trump's presidency are, to China's current rulers, a profound vindication of their darkest earlier assessments of U.S. policy.

But Trump has turned what Beijing perceived as a long-term risk into an immediate crisis that demands the urgent mobilization of the Chinese system. The Trump administration has sought to weaken the grip of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on society, force the liberalization of the state-dominated Chinese economic system, and block China's drive to technological supremacy. Nearly four years into this gambit, however, Trump's policies appear to have produced the opposite result in each domain.

Washington needs a China strategy that not only assesses Chinese capabilities and aims but also takes full account of the way China's leaders understand the United States and have reacted to Trump's presidency. This strategy must also reject the faddish but inaccurate notion that China is somehow an impervious force, advancing on an immutable course and unresponsive to external pressure and incentives. The United States can craft a strategy that much more effectively deters China's most problematic behavior. But to do so, Washington must endeavor to upend Chinese leaders' assumption that the United States is inexorably declining.

"THE WOLF IS COMING"

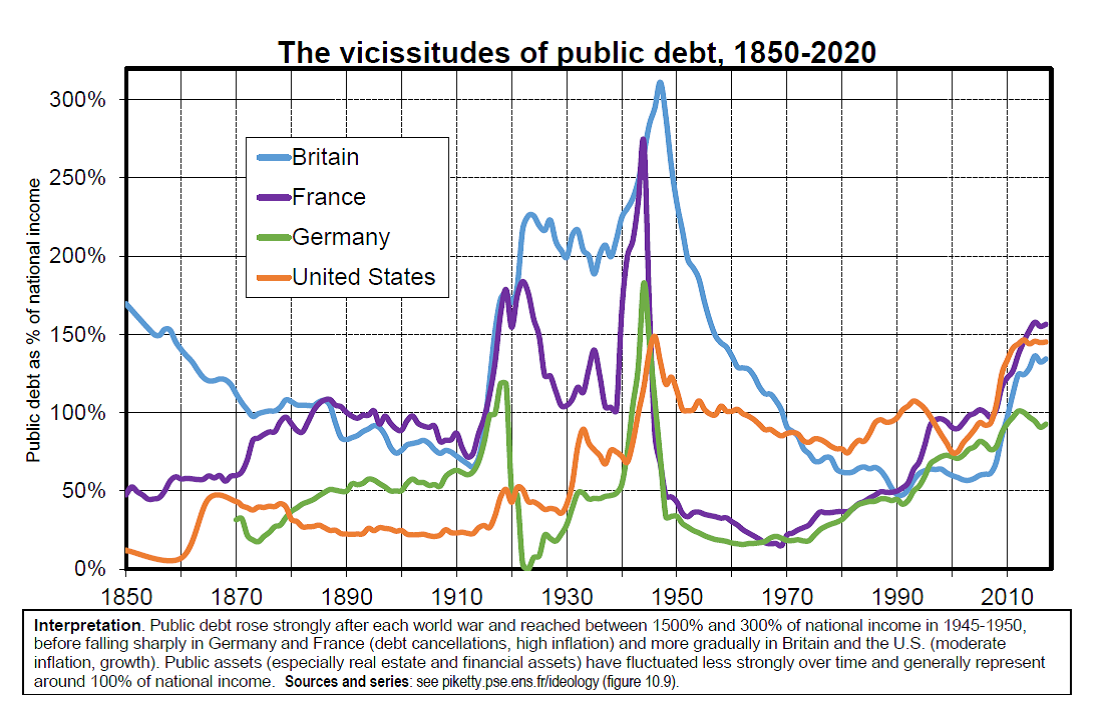

Chinese leaders and policymakers have believed for decades that U.S. power is waning and that the United States seeks to impede China's rise. Mao Zedong was fond of predicting the decline of the capitalist world led by the United States, comparing it to "a dying person who is sinking fast." He regularly attacked Western attempts to subvert China's communist revolution, denouncing "reactionaries trying to hold back the wheel of history." These ideas outlived Mao, although they were shaken as the CCP embraced market reforms and as the United States emerged as the sole superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union. But the 2008 financial crisis, which left China relatively unscathed, caused the country's leaders to wonder whether the ruinous decline of capitalism that Mao had predicted had in fact arrived. And with their Marxist-inflected view of historical forces, they expected that this prospect would lead, as night follows day, to the flailing of Mao's hopeless "reactionaries"—American leaders who would try in vain to hold China down.

These ideas shaped the worldview of Chinese President Xi Jinping. When he came to power in 2012, he spoke of historical patterns of conflict between rising and fading hegemonic powers, warned about the U.S. role in hastening the collapse of the Soviet Union, and promoted such figures as Wang Huning, a former law professor and longtime government adviser whose best-known book, America Against America, highlighted how far the United States fell short of its ideals. But Xi and his lieutenants were initially more focused on addressing the political and ideological fragility of the system they inherited; they expected the decay of the United States to be gradual.

Many Chinese elites now think that Trump's presidency has pushed that slow process into a new phase of sharp and irreversible deterioration. They took measure of the president's withdrawal from international agreements and institutions and his disdain for traditional alliances. They saw how U.S. domestic policies were exacerbating inequality and polarization, keeping out immigrants, and cutting federal funding for research and development. Wu Xinbo, the dean of Fudan University's Institute for International Studies, argued in 2018 that the "unwise policies" of the Trump administration were "accelerating and intensifying [U.S.] decline" and "have greatly weakened [the United States'] international status and influence." A commentary in the Beijing-backed newspaper Ta Kung Pao earlier this year held that "America is moving from 'declining' to 'declining faster.'" This belief has become a central premise of China's evolving strategy toward the United States.

Chinese leaders have believed for decades that the United States is a waning power.

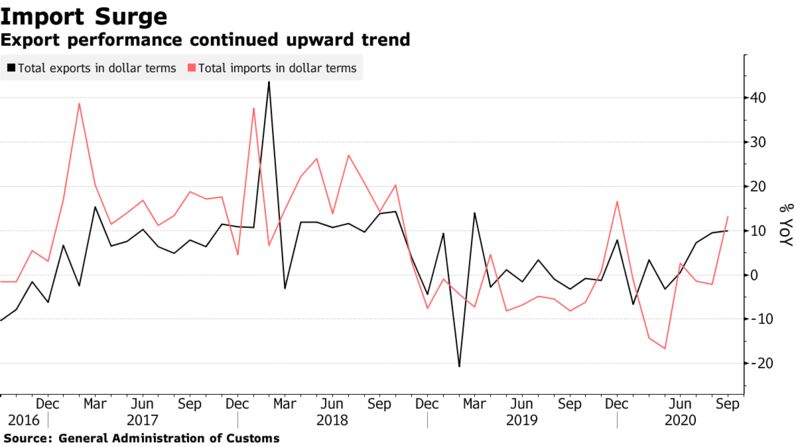

CCP leaders connect this rapid American decline to intensified U.S. efforts to contain China; the United States under Trump has gone from being a latent, long-term menace to the source of concerted efforts to, in the favored phrase of Chinese officialdom, "comprehensively suppress" China. In 2018, Trump slapped tariffs on tens of billions of dollars' worth of Chinese goods and issued bans on the Chinese telecommunications firms Huawei and ZTE. (Although Trump eventually reversed his ZTE decision as a favor to Xi, the threat to the company—which relied on the United States for approximately one-quarter of the components in its equipment—was existential; analysts have described more recent measures against Huawei, similarly, as a "death sentence.") The rhetoric of past and present Trump advisers, such as Peter Navarro (whose books include The Coming China Wars and Death by China) and Steve Bannon (who called for "regime change in Beijing"), helps vindicate the darkest, most conspiratorial notions among the Chinese leadership.

Trump's actions and rhetoric have solidified Beijing's assessment that there is now a durable American effort underway to quickly suppress China, and Chinese leaders see that effort as bipartisan, too, with near-unanimous congressional votes on legislation related to China and criticisms of China coming from prominent Democrats, such as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. An editorial from this past July in the Chinese state-run newspaper Global Times stated, "China must accept the reality that America's attitude toward China has fundamentally changed." The shift in elite opinion in China is clear. According to Wei Jianguo, a former top Chinese trade official, the prevailing view in Beijing is that "the essence of the trade war is that the United States wants to destroy China." Fu Ying, a senior diplomat, declared in June that the United States' goal for China is now clearly "to slow it down through suppression," a fight that the declining superpower "can't afford to lose." The Foreign Ministry's spokesperson, Zhao Lijian, declared in August that the United States is "a far cry from the major power it used to be," with its leaders bent on "working to suppress China because they fear China's growth." These ideas are remarkably widespread in the statements of Chinese officials and experts, the pages of CCP magazines and newspapers, and across Chinese social media.

Chinese leaders have long thought that this confrontation might arrive someday, but it has come much quicker than they expected. "People in the United States and China have for years said the wolf is coming, the wolf is coming, but the wolf hasn't come," Shi Yinhong, a leading international relations scholar, told The New York Times. "This time, the wolf is coming."

EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

With such perceptions entrenched, it should come as no surprise that China has reacted in ways that are leading to further conflict between the already divergent U.S. and Chinese systems. Since Xi's ascent, China's ever more authoritarian and domineering turn has alarmed governments around the world. In 2018, Xi removed term limits on his office. Under his watch, the CCP has more openly embraced its illiberal identity, pairing repression at home—most gruesomely in Xinjiang, where internment camps hold more than one million Uighurs and members of other minority ethnic groups—with loud criticism of democracies abroad. Despite U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's call to "engage and empower the Chinese people" against the CCP—an appeal widely interpreted in China as a bid for regime change—the party's hold over society remains strong. It rolled out new ideological and political campaigns this past summer. The clampdown that accompanied China's response to the COVID-19 pandemic has further bolstered Beijing's surveillance and social control systems.

Some top U.S. officials have maintained that the goal of Trump's policy is to force the liberalization of China's state-dominated economic system, but from the outset of the trade war in 2018, the Chinese government judged that Trump's goals were mercantilist—he cared only about getting a so-called good deal for the United States. In response, China's rulers have redoubled their reliance on the state sector to deal with the instability resulting from conflict with the United States. Since the early years of Xi's tenure, state-owned enterprises have benefited from increasingly favorable government policies and preferential bank lending, often at the expense of private firms. One economist with strong links to the CCP elite told me that he and many of his colleagues initially believed that Trump's trade war was a positive development because they thought it would reverse this trend and revive market reform. But the trade war has had the opposite effect: Xi has doubled down on building "stronger, better, and larger" state-owned enterprises and rejecting the deeper economic liberalization that officials around the world have long sought in China.

In trade negotiations that reached a limited "Phase 1" agreement in January of this year, Beijing agreed to a series of pledges to buy U.S. goods, rather than to any significant new commitments to reform. Chinese state media reports even floated upgrading the state-dominated economic model to the status of one of China's "core interests"—a sacrosanct category usually reserved for territorial and sovereignty claims. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored to many in China the advantages of this model, with the Xinhua News Agency announcing that state-owned enterprises "have been a vital force and the main force" in responding to the pandemic.

Far from curbing China's push for technological supremacy, Trump's actions have encouraged its leaders to accelerate their drive to reduce their country's dependence on the United States. For many years, China has tried to balance between reaping the benefits of interdependence and insulating itself from the risks of being the weaker partner in its relationship with the world's most powerful country. After Xi came to power, he made it a priority to address the dangers of interdependence, including through the "Made in China 2025" initiative, which aims to make China 70 percent self-sufficient in ten core technologies by the year 2025. Xi has proved willing to sacrifice economic growth in the name of national autonomy, and a range of cosmopolitan officials and government-linked experts who once supported greater integration have come to agree with him. Li Qingsi, the executive director of the Center for American Studies at Renmin University of China, wrote that the ZTE case in 2018 "disillusion[ed] those who advocate relying on the United States to develop our own economy" and drove home the lesson that "China must carry forward the tradition of self-reliance and reduce external dependence."

Beijing is finding it hard to speed up its self-sufficiency drive, but the direction is clear. A world in which China truly becomes self-reliant is a world in which the United States has much less leverage over China than it does at present. China is still dependent on foreign firms for many foundational technologies, including the cutting-edge semiconductors needed for everything from personal computers and smartphones to artificial intelligence systems. In 2019, Chinese leaders stopped talking publicly about Made in China 2025 to reduce tensions during negotiations with the United States, but the policy endures in substance, and one anonymous senior official told an American journalist that the CCP "will never give an inch" on the scheme's broader goals. Earlier this year, Xi pledged a further $1.4 trillion to invest in the development and deployment of advanced technological infrastructure such as 5G wireless networks, enhanced sensors and cameras, and automation.

Chinese concerns about dependency on the United States also extend more widely. Tensions have recently become especially high around U.S. dominance of international finance, from the use of the dollar to interbank payment systems. Even internationalist officials, such as the former finance minister Lou Jiwei, have started warning about the risk of a "financial war" and about the United States doing "everything in its power to use bullying measures [and] long-arm jurisdiction" against China.

Leaders in Beijing believe that a declining United States will seek to suppress China's rise.

Chinese elites describe the COVID-19 pandemic as proof that the United States will lash out at China as it plunges into decline. Trump's failure to control the disease, with around six million cases and nearly 200,000 deaths in the United States by the end of August, reflects what Chinese commentators see as the parlous state of the country. They have called the pandemic "Waterloo for America's leadership" and "the end of the American century." They believe that Trump launched his election-season push against China—he has called COVID-19 "the plague from China" and issued new sanctions and other measures targeting Chinese entities—to distract from the failings of his administration. But many leading Chinese voices are convinced that whatever the result of the U.S. presidential election, the trajectory of U.S.-Chinese relations is now set by the inexorable forces of American decline and hostility to China. "Even if Biden wins," Yuan Peng, the influential president of the Ministry of State Security's China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, recently wrote, ". . . America will have a hard time reassuming its role as a world leader . . . and America's China policy will only get increasingly hyper-sensitive, unyielding, and arrogant as they double down on containment and suppression."

Xi is rolling out new policies that are based on these expectations. Beginning this past spring, he unveiled an agenda for the economy that aims to reorient China's economic development inward, relying much more on China's enormous domestic market and less on the "more unstable and uncertain world." Fostering domestic demand has long been a talking point of Chinese leaders, but Xi has pledged to make achieving greater domestic consumption a centerpiece of the upcoming five-year plan for 2021–25. This shift is clearly driven by the assumption that the United States will continue working against China. As one state media outlet declared pointedly in late July, "No country and no individual can stop the historic pace of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation."

To be sure, Xi would like to de-escalate the trade and technology conflicts with the United States to buy time. He also wants China to strengthen and diversify its ties to other economies around the world, including through the Belt and Road Initiative, an international network of infrastructure projects that aims to increase China's geopolitical influence. China is not deglobalizing as much as it is de-Americanizing.

China's conviction that the United States is a diminishing and hostile power has emboldened its leaders to pursue long-standing objectives with new vigor. Their view of U.S. decline makes them see fewer risks in taking highly aggressive positions, and their sense of U.S. hostility, among other factors, increases their willingness to incur international opprobrium: imposing a new national security law on Hong Kong; committing atrocities in Xinjiang; bullying Australia, India, and the Philippines; threatening Taiwan; forging new partnerships with Iran and Russia; and letting Chinese diplomats spread conspiracy theories about the origins of COVID-19. With the United States withdrawing from multilateralism and international institutions, China has tried to reshape global bodies, such as the UN Human Rights Council, in its favor. China's behavior in these areas is often at odds with U.S. interests and a rules-based order, with Beijing flouting rules it dislikes and undermining liberal norms and values.

A BETTER CHINA STRATEGY

How should U.S. strategy toward China grapple with these changes? Given the dismal track record of the past several years, some may be tempted to try to undo these shifts by reassuring Beijing that the United States does not in fact intend to keep China down. This path is highly unlikely to succeed. China's ambitions conflict with U.S. interests in many areas—and with Trump confirming so much of Beijing's view of the United States, no amount of diplomatic reassurance can convince China's leaders to give up their quest for security through strengthening their control over society, shoring up the statist economic system, and reducing China's dependence on the United States. Attempting to persuade them otherwise at this point would seem only to be cheap talk, at odds with their perception of "the wheel of history" turning faster toward American decline. U.S. strategy must seek to move forward, not backward, from the current predicament.

But that does not mean Beijing's entire agenda is immutable. This view is much in vogue today, casting China not as a country that responds to pressure and incentives but as an adamantine force incapable of reacting to external stimuli. Yet it would be wrong to conclude that the unsuccessful policies of the past several years mean that the United States is somehow helpless in the face of a more powerful China, only able to pull up the drawbridge, prepare for conflict, and hope that the CCP collapses. A different approach—neither a nostalgic "reset" nor that fearful and fatalistic vision—is needed.

The best path forward is to craft a strategy premised on a more realistic assessment of both U.S. and Chinese interests. Beijing sees the world in harshly competitive and ideological terms, but Washington can still advance its interests with respect to China. The most ambitious—and most important—aspect of this strategy must be showing China and the rest of the world that the United States remains strong and can reliably revive the sources of its power and leadership. China's rulers have built their strategy on a profound underestimation of the United States. By upending the exaggerated reports of its demise, the United States could change China's calculus and find a way toward sustainable coexistence on favorable terms.

Nothing is as important to competing effectively with China as what the United States does at home, revitalizing its economic fundamentals, technological edge, and democratic system. All these initiatives would be important even in the absence of competition with China, but the rivalry with Beijing adds to their urgency. Policymakers must get the COVID-19 crisis under control, implement economic policies that benefit all Americans, welcome immigrants who enrich U.S. society, pursue racial justice to show the world that U.S. democracy can remain a beacon of freedom and equality, make smart investments in U.S. defense capabilities, and scale up federal funding for research and development. This ambitious agenda for national renewal and resilience would profoundly shake the foundations of the CCP's strategy. U.S. leaders should also not shy away from publicly pointing out authoritarian China's many weaknesses, including the country's aging population, ecological crises, numerous border disputes, and declining international popularity.

The United States must also band together with allies and partners in Asia and Europe to push back against problematic Chinese behavior. That effort should include using joint economic leverage to punish firms and groups that steal intellectual property and engage in other unfair and illegal conduct; strengthening military capabilities and showing increased resolve in the face of Chinese aggression; and sanctioning institutions and officials that are aiding repression in Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xinjiang. They should also work to revitalize the international institutions and those elements of the rules-based order that can limit the competition between states. Playing defense, the United States and its partners need to take steps to maintain their leverage in key areas of international trade while disentangling themselves entirely from supply chains that create unacceptable vulnerabilities to China (such as the production of critical medical supplies) and diversifying away from those for which the danger is less serious. Not all risks are equally significant, however, and the United States and its democratic allies are open societies that still stand to gain from economic, scientific, and people-to-people exchanges with countries around the world, including China, even as they do more to guard against coercion and espionage from foreign rivals.

The United States and China also have important shared interests and should strive to prevent the worst outcomes of their competition. Both countries must confront profound challenges such as climate change, pandemic disease, and nuclear proliferation, which cannot be met without coordination and joint action. U.S. and Chinese leaders should also work to head off foreseeable disasters, such as the looming risk of cyberwar and the prospect of a conflict in the contested South China Sea. In these most volatile and dangerous areas, they should negotiate redlines and effective mechanisms for crisis management and de-escalation. By working with China on these issues when necessary, even in the context of an intensely competitive relationship, the United States would show Beijing that it does not fear or seek to contain a prosperous China that takes on a major global role and plays by the rules. Over time, such steps could also eventually create space for China's leaders to decide that addressing these urgent shared problems is more important than believing their own paranoid visions of the United States.

But all these efforts will pay off fully only if the United States can demonstrate how mistaken the CCP is about the notion of inexorable U.S. decline. Achieving clarity about the task ahead would itself be a reason for optimism. The Chinese leadership's dark view of the prospects for the United States is wrong. The United States is not trapped by old ways of addressing problems or borne along by historical forces beyond its power to shape. Much of what the United States must do to compete effectively with China is within its control—and there is still time to act.