https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/lebron-jamess-i-promise-school-puts-public-face-evidence-based-approach-whole-family-intervention

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Our era is ripe for change. Neoliberalism is politically and morally bankrupt, yet a new vision for economic policymaking in the 21st century has yet to be fully articulated, let alone become a convincing alternative to the neoliberal model. |

, Anawat Sudchanham/EyeEm/Getty Images |

or the past forty-five or so years, progressive economic policy in the advanced capitalist societies has not only been losing ground steadily to neoliberal economic actions and outlooks but is in real danger of becoming a thing of the past. The result – in spite of a strong US stock market performance and low interest rates — has been anemic growth (growth rates during the neoliberal era have been cut in half in comparison to growth rates during the 1950s and 1960s), massive unemployment in many European countries, huge levels of inequality, declining standards of living (with the US being very close to the top of the list) and growing immerization, all of which have provided fertile ground for the emergence of far-right and extreme nationalist movements which, interestingly enough, seem to promise voters a return to the "golden age" of capitalism. By "progressive economic policy," I mean those actions aimed at establishing a regulated and mildly egalitarian form of capitalism through the use of government power. The ultimate aim of progressive economics is to provide higher incomes for and better standards of living for average workers. Progressive economics should not be conflated with socialism. Progressive economics may be seen as representing an offshoot of the socialist tradition, but only under certain sociopolitical settings, as in the case, perhaps, of the Nordic countries. By "neoliberal economics," I mean those policies that promote deregulation of the economy and seek to shift the orientation of the state as far away as possible from redistribution and a socially-based agenda, and toward strengthening the interests of finance capital and the rich. Having said that, it should also be pointed out that neoliberal economics should not be seen as a natural offshoot of classical economics, but rather as a distinct 20th-century movement guided by antistatist views and an explicitly antilabor outlook. This is the version of neoliberalism developed by Milton Friedman and the so-called Chicago School, and is usually associated with the Pinochet regime in Chile and later on with the free-market policies of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. In the United States, the adoption of neoliberalism as an economic model coincides with the deindustrialization period, which undermined the economy's industrial base and undercut the power and influence of the labor movement, and was solidified during Reagan's years in power. It can be argued that, in the course of the 20th century, the United States has had only two administrations that pursued determinately progressive economic policymaking: those of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, with the New Deal programs, and of Lyndon Johnson, with the Great Society programs. In an interesting twist of history, Richard Nixon was perhaps the last "liberal" US president on the economic and social front. In Europe — save England, where Thatcher launched the neoliberal economic counterrevolution at about the same time Reagan was elected president — the shift occurs a bit later: around the mid-1980s in nations like Germany and France, and even a bit later in the peripheral countries of Europe like Greece and Spain. By the mid-1990s, most western European societies, with the exception of the Scandinavian countries, can be roughly characterized as being neoliberal. The abrupt transition to neoliberal economic policymaking in Europe is enshrined in the 1992 Treaty of the European Union, also known as the Maastricht Treaty. The story of the rise of neoliberalism has been told in countless ways and from myriad points of view in the course of the last forty-five or so years. Still, oversimplifications of the actual meaning of neoliberalism abound and ideological biases often enough get in the way of lucid and dispassionate analyses. In a way, this is because neoliberalism itself is more of an ideological construct than a solidly grounded theoretical approach or an empirically derived methodology. In fact, the intellectual foundations of neoliberal discourse are couched in profusely vague claims and ahistorical terms. Notions such as "free markets," "economic efficiency," and "perfect competition" are so devoid of any empirical reference that they belong to a discourse on metaphysics, not economics. Essentially, neoliberalism reflects the rise of a global economic elite and is used mostly as an ideological tool to defend the interests of a particular faction of the capitalist class: that of finance capital. The neoliberal transition in the world economy is associated, then, with the rise to dominance of financial capital and the sharp changes that occur in the social structure of capital accumulation, with developments in the US economy leading the way among advanced capitalist economies. Indeed, financialization, although not synonymous with neoliberalism, is a key feature of the latter. The economic slowdown in the 1970s and the inflationary pressures that went along with the first major postwar systemic capitalist crisis created a window of opportunity for antistatist economic thinking, which had been around since the 1920s but was spending most of its time hibernating because it lacked support among government and policymaking circles and had very few followers among the members of the chattering classes. The postwar capitalist era was dominated by the belief that the government had a crucial role to play in economic and societal development. This was part of the Keynesian legacy, even though Keynesian economics was never fully and consistently applied in any capitalist country. Industrial capitalism, the production of real goods and services for the benefit of all members of a society, required extensive government intervention; both as a means to sustain capital accumulation and as a way to ensure that the toiling population improved its standard of living so it could purchase the goods and services that its own members produced in the great factories of the Western industrial corporations. The rise of the middle class in the West took place predominantly in the first fifteen years or so after World War II and was an outcome brought about by the combination of a thriving Western capitalist industrial base and interventionist government policies. Governments and the industrial capitalist classes understood only too well that economic growth and social prosperity had to go hand in hand if the system of industrial capitalism was to survive. Maintaining "social peace," a long sought after objective of governments and economic elites throughout the world, mandated that the wealth of a nation actually trickled down to the members of the toiling population. The improvement of the working class's standard of living was essential to the further growth of industrial capital accumulation. To be sure, it took at least a couple of centuries before industrial capitalism reached a stage where its own survival and future growth were predicated on a steady increase of living standards among a nation's general population. In postwar capitalist economies, providing the working class with the means for their reproduction meant increasingly improving their economic purchasing power and providing them with access to educational opportunities, so they could make a substantially greater contribution to productivity while also being turned into potential consumers. In all this, the government had a key role to play as it was the only agent with the capability of providing the opportunities and the resources needed for the materialization of a society of plenty; a society in which the fruits of labor were not the exclusive domain of the class that owned the means of production. All this came to a rather abrupt end sometime around the mid-to-late 1970s, when advanced capitalism found itself in the grips of a major systemic crisis brought about by new technological innovations and declining rates of profit. The social structures of accumulation that had emerged after the Second World War began to dissolve. Policy shifted in the direction of unregulated markets as a means of overcoming the declining rate of profit, while the "welfare state" was in the process of being dismantled. In this context, the postwar regime of "managed capitalism" gave way to "unfettered markets," and a capital globalization process ensued that today encompasses virtually all economies in the world. The Neoliberal Nightmare and Thinking Our Way Out of It At the heart of the neoliberal vision is a societal and world order based on the prioritization of corporate power and free markets and the privatization of public services. The neoliberal claim is that economies would perform more effectively, producing greater wealth and economic prosperity for all, if markets were allowed to perform their functions without government intervention. This claim is predicated on the idea that free markets are inherently just and can create effective low-cost ways to produce consumer goods and services. By extension, an interventionist or state-managed economy is regarded as wasteful and inefficient, choking off growth and expansion by constraining innovation and the entrepreneurial spirit. However, the facts say otherwise. During the period known as "state-managed capitalism" (roughly from 1945–73, and otherwise known as the classical Keynesian era), the Western capitalist economies were growing faster than at any other time in the 20th century and wealth was reaching those at the bottom of the social pyramid more effectively than ever before. Convergence was also far greater during this period than it has been during the last forty-five or so years of neoliberal policies. Moreover, under the neoliberal economic order, Western capitalist economies have not only failed to match the trends, growth patterns, and distributional effects experienced under "managed capitalism," but the "free-market" orthodoxy has produced a series of never-ending financial crises, distorted developments in the real economy, elevated inequality to new historical heights, and eroded civic virtues and democratic values. In fact, neoliberalism has turned out to be the new dystopia of the contemporary world. Our era is ripe for change. Neoliberalism is politically and morally bankrupt, yet a new vision for economic policymaking in the 21st century has yet to be fully articulated, let alone become a convincing alternative to the neoliberal model. In this regard, progressive economics that go beyond the policies advocated by Keynes himself, particularly ideas such as workers' participation, income distribution, sustainable development, and environmentally friendly policies, can be of vital importance in galvanizing public support for a new socioeconomic order. Contrary to radical neoliberal political discourse, the state has not disappeared under the process of globalization; nor has it become weaker. It has merely been refocused so it can perform activities more amenable to the needs and demands of the global financial elite. The state, as a social institution, does retain a certain degree of relative autonomy, and thus it can be recaptured by progressive forces determined enough to work toward the realization of a just and decent society, instead of standing idly by and watching elected public officials squander the common good (officials eager to get into office in order to serve big business interests so they can later pursue lucrative private sector roles). The most critical issues facing advanced industrialized societies today are the power that finance capital exerts over the domestic economy and the social ills it frequently causes due to financial busts, financial scandals, and plain untamed greed. Finance capital is economically anti-productive (it does not create real wealth as such), socially parasitic (it lives off revenues produced in other sectors of the economy), and politically antidemocratic (it places constraints on the distribution of wealth, creates unparalleled inequality, and strives for exclusive privileges). The future of Western liberal societies may very well depend on radical changes regarding the relationship between government and finance capital, government and the military-industrial complex, and the ways through which the public sector approaches development and employment. State power needs to be reaffirmed from the perspective of the advancement of a nation's general welfare, and thus must cease being a tool of finance capital and of the global economic elite. In order for that to happen, public discourse needs to be energized and involve the widespread participation of citizens and communities. In this regard, a progressive political economy to economic and social problems facing the 21st century must entail the utilization of participatory democracy as an essential and irreducible factor in the design and materialization of a new socioeconomic order beyond global neoliberalism. For the truth of the matter is that the dominance of finance capital has caused severe blows not only to economic development as such but to democratic political culture and society as a whole. Democracy is at a stage of steep and long-term decline and, as political scientist Larry Bartels argues, the "general will" has been transformed into an exclusive privilege of the superrich and powerful among us. Finance capital should no longer be allowed to define the terms of the game on the basis of its own needs and interests, and should retreat into serving the needs of the real economy. The current levels of public and private debt are too big for a recovery to take place, and all future policies aimed at sustainable development are certain to fail if the issue of debt is not addressed, mainly through a huge write-down. Under the current levels of debt accumulated by most advanced industrialized societies, austerity will be increasingly seen as a necessary condition for economic stabilization, causing further economic decline and greater debt-to-GDP ratios in the end. In this manner, a major debt restructuring plan should be put on the public agenda of all industrialized economies around the world, along with the design of a new global financial architecture in the interests of the real economies and the economics of environmental sustainability and social development. What is required is a vision of a humane socio-economic order and the subsequent taming of the aggressive, socially destructive pursuit of private interests. For that to happen, the Left must restore a sense of the common good on the basis of an unashamedly declared progressive economic policy, with class at its core, and return to the principles and values of universal human rights. As things stand, the global capitalist economy and contemporary western societies in general function in a very asymmetrical and dangerous manner: the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. Global neoliberalism suppresses wages, increases inequality, and destroys the social fabric. Capitalism is a socioeconomic system in dire need of a replacement, and a new social order is very much needed. In this manner, the responsibility falls clearly on progressive political economy to chart a full-fledged alternative course, with UNCTAD's 2017 Trade and Development Report, titled Beyond Austerity: Towards a Global New Deal, providing a possible starting point. Policy Recommendations Going forward, here are the principles and priorities that could provide the framework for the implementation of transformative progressive economic policies.

Note: This article is a revised version of a policy paper that originally appeared as a Levy Institute publication. C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism's politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout's Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish. He is the author of Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books. |

Recent links to WaPo pieces:

Productivity and wages: They're connected, of course, but the extent of the connection requires nuanced analysis of wages at different percentiles and movements in labor's share of national income.

There's an interesting dichotomy here in how economists and people think about productivity and wages. For many economists, it's the determinant of wage growth. For many people, it's irrelevant, in that powerful forces divert productivity growth from paychecks to profits. The truth, especially once you get away from averages, lies in-between. Productivity matters a great deal, but it is not by itself sufficient to drive broadly shared prosperity.

Employment rates also matter a lot: They take the elevator down in recessions and the stairs up in recoveries. They also may carry some info about the arrival of next recession. Plus, their recent movements reveal the disproportionate benefits of full employment to the least advantaged.

Are politicians no longer listening to economists? You wish. In fact, they're listening to the wrong ones telling them what they want to hear.

Now, a quick note on current events.

As regards the tanking of the Turkish lira, the business press is largely concerned with the contagion question: to what extent will Turkey's problems spillover into European and American economies? The consensus is "not much," based on Turkey's size and financial markets' limited exposure to Turkish debt, much of which is dollar-denominated, meaning it becomes more expensive to service when the Turkish currency depreciates.

That's probably right, and Turkey has uniquely weak fundamentals among emerging market economies: "current account deficit of 6.3% of GDP, Corporate foreign exchange debt is 35% of GDP, inflation rate of 16%." But the situation bears close watching, of course, and the strengthening dollar has important implications for the trade war, i.e., it pushes in the opposite direction of the tariffs (tariffs make imports more expensive; the stronger dollar makes them less expensive).

But another interesting aspect of the Turkish meltdown is how much Trump and Erdogan have in common. In one sense, that's not surprising, as the strongman, faux populist playbook is pretty straightforward, and history is replete with examples.

In this case, Trump and Erdogan both pursue: reckless fiscal policy, muscling the central bank to keep rates down (though Trump doesn't use anything like the muscle that Ergodan does), appointing family members to high places (sons-in-law, to be specific), vilifying other countries/media as the source of any woes (in a Trumpian flourish, Erdogan recently blamed "economic terrorists on social media" for spreading misinformation).

And yet, the economic outcomes, particularly via the currency and capital flows couldn't be more different. In fact, the relative currency moves show foreign exchange traders are pulling out of the riskier emerging markets and buying dollars and U.S. debt.

It's a reminder of the do

Marti Sandbu: EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts, by Ashoka Mody: "Writing about the euro... doing justice to the technicalities threatens to kill any narrative, while simplified storytelling risks misguided analysis. Ashoka Mody's... is an ambitious attempt to avoid this trap...

We really do not know what effect a trade war would have on the global economy. All of our baselines are based off of what has happened in the past, long before the age of highly integrated global value chains. It could be small. It could be big. The real forecast is: we just do not yet know: Dan McCrum: Trade tension and China : "The war on trade started by the Trump administration is percolating through the world's analytical apparatus.... Tariffs could be bad for the global pace of economic activity, but only if the economic warfare escalates...

It has always seemed to me that the sharp Josh Bivens is engaging in some motivated reasoning here: "[1] Putting pen-to-paper on trade agreements contributed nothing to aggregate job loss in American manufacturing. This is almost certainly true.... [2] The trade agreements we have signed are mostly good policy and have had only very modest regressive downsides for American workers. This is false." How am I supposed to reconcile [1] and [2] here?: Josh Bivens (2017): Brad DeLong is far too lenient on trade policy's role in generating economic distress for American workers on Brad DeLong(2017): NAFTA and other trade deals have not gutted American manufacturing—period: "I could rant with the best of them about our failure to be a capital-exporting nation financing the industrialization of the world...

Early industrial Japan did marvelous things. It accomplished something unique: transferring enough industrial technology outside of the charmed circles of the North Atlantic and the temperate-climate European settler economies. Ever since, politicians, economists, and pretty much everybody else have been trying to determine just what it was Japan was ale to do, and why. But it was a low-wage semi-industrial civilization, economizing on land, materials, and capital and sweating labor: Pietra Rivoli (2005): The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Markets, Power, and Politics of World Trade (New York: John Riley: 0470456426) https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0470456426: "Female cotton workers in prewar Japan were referred to as 'birds in a cage'...

Edith Laget, Alberto Osnago, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta: Trade agreements and global production: "Deeper agreements have boosted countries' participation in global value chains and helped them integrate in industries with higher levels of value added. Investment and competition now drive global value chain participation in North-South relationships, while removing traditional barriers remains important for South-South relationships...

Wealth inequality measures have been grossly understating concentration because of tax evasion and tax avoidance in tax havens: Annette Alstadsæter, Niels Johannesen, and GabrielZucman: Who owns the wealth in tax havens? Macro evidence and implications for global inequality: "This paper estimates the amount of household wealth owned by each country in offshore tax havens...

Jared Bernstein: [Trump did a bunch of stuff to strengthen the dollar; now he's upset about the strengthening dollar(https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2018/07/20/trump-did-a-bunch-of-stuff-to-strengthen-the-dollar-nows-hes-upset-about-the-strengthening-dollar/?noredirect=on&utmterm=.576fbc1e4803)_: "Trump is annoyed that the Fed is raising rates and that the stronger dollar is making our exports less competitive...

Paul Krugman: Brexit Meets Gravity: "These days I'm writing a lot about trade policy. I know there are more crucial topics, like Alan Dershowitz. Maybe a few other things? But getting and spending go on; and to be honest, in a way I'm doing trade issues as a form of therapy and/or escapism, focusing on stuff I know as a break from the grim political news...

A Britain led by Theresa May or Boris Johnson or Jeremy Corbin will not "rediscover its own way... the British rae most resilient, most inventive, and happiest when they feel in control of their own future". That is simply wrong. And if it were right, May and Johnson and Corbin are not Churchill or Lloyd-George or even Salisbury: Robert Skidelsky: The British History of Brexit: "I am unpersuaded by the Remain argument that leaving the EU would be economically catastrophic for Britain...

Paul Krugman: "Maybe it's worth laying out the incoherence of Trump's trade war a bit more, um, coherently...

IMHO, betting that "even the Tory Party can spot a wrong 'un" seems a lot like drawing to an inside straight: Dan Davies: "The hard brexit types have been bounced into deal which has taught them that they're not as clever as they thought they were. Now they'll react to that with a leadership challenge which will teach them that they're not as popular as they thought they were. It's like education in the Montessori system-each little independence of discovery builds on the next..."

Anne Applebaum: Brexit is reaching its grim moment of truth—and the Brexiteers know it: "David Davis... and Boris Johnson.... At no point... have they or any of their Brexiteer colleagues offered what might be described as a viable alternative plan. That is because there isn't one...

Trade around the Indian Ocean before 1500 was a largely peaceful, stable process. Empires, kingdoms, sultanates, and emirates ruled the lands around the ocean, but they did not have the naval strength or the orientation to even think of trying to control the ocean's trade. Pirates were pirates—but only attacked weak targets, and needed bases, and for the land-based kingdoms providing bases for pirates disrupted their own trade. Then came 1500, and a new entity appeared in the Indian Ocean: the Portuguese seaborne empire: [Non-Market Actors in a Market Economy: A Historical Parable): From David Abernethy (2000), The Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires 1415-1980 (New Haven: Yale), p. 242 ff: "Malacca... located on the Malayan side of the narrow strait... the principal center for maritime trade among Indian Ocean emporia, the Spice Islands, and China...

Alex Barker and Peter Campbell: Honda faces the real cost of Brexit in a former Spitfire plant: "Honda operates two cavernous warehouses.... They still only store enough kit to keep production of the Honda Civic rolling for 36 hours...

The big problem China will face in a decade is this: an aging near-absolute monarch who does not dare dismount is itself a huge source of instability. The problem is worse than the standard historical pattern that imperial succession has never delivered more than five good emperors in a row. The problem is the again of a formerly good emperor. Before modern medicine one could hope that the time of chaos between when the grip on the reins of the old emperor loosened and the grip of the new emperor tightened would be short. But in the age of modern medicine that is certainly not the way to bet. Thus monarchy looks no more attractive than demagoguery today. We can help to build or restore or remember our "republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government". An autocracy faced with the succession and the dotage problems does not have this option. Once they abandon collective aristocratic leadership in order to manage the succession problem, I see little possibility of a solution. And this brings me to Martin Wolf. China's current trajectory is not designed to generate durable political stability: Martin Wolf: How the west should judge the claimsof a rising China: "Chinese political stability is fragile...

Brad Setser: "Larry Summers on Trump and trade:: 'From tweet to tweet, official to official, nobody can tell what his priorities are.' Certainly rings true to me. I have almost stopped trying to guess. Even for China:"

A new scientific paper proposing a scenario of unstoppable climate change has gone viral, thanks to its evocative description of a "Hothouse Earth". Much of the media coverage suggests that we face an imminent and unavoidable extreme climate catastrophe. But as a climate scientist who has carried out similar research myself, I am aware that this latest work is a lot more nuanced than the headlines imply. So what does the hothouse paper actually say, and how did the authors draw their conclusions?

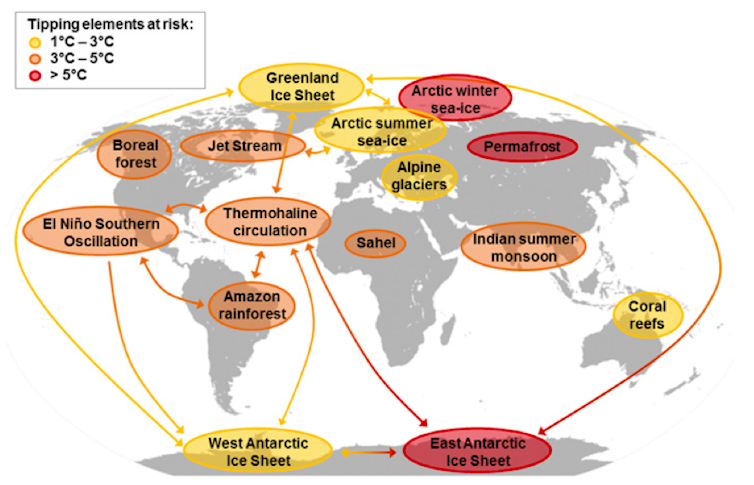

First, it's important to note that the paper is a "perspective" piece – an essay based on knowledge of the scientific literature, rather than new modelling or data analysis. Leading Earth System scientist Will Steffenand his 15 co-authors draw on a diverse set of literature to paint a picture of how a chain of self-reinforcing changes might potentially be initiated, eventually leading to very large climate warming and sea level rise.

One example would be the thawing of Arctic permafrost, which releases methane into the atmosphere. As methane is a greenhouse gas, this means the Earth retains more heat, causing more permafrost to thaw, and so on. Other possible self-reinforcing processes include the large-scale die-back of forests, the melting of sea ice, or the loss of ice sheets on land.

Global map of potential tipping cascades, with arrows showing potential interactions. Steffen et al / PNAS

Global map of potential tipping cascades, with arrows showing potential interactions. Steffen et al / PNASSteffen and colleagues introduce the term "Hothouse Earth" to emphasise that these extreme conditions would be outside those that have occurred over the past few hundred thousand years, which have been cycles of ice ages with milder periods in between. They also present an alternative scenario of a "Stabilised Earth" where these changes are not triggered, and the climate remains similar to now.

The authors make the case that there is a level of global warming which is a critical threshold between these two scenarios. Beyond this point, the Earth System might conceivably become set on a pathway that makes the extreme "hothouse" conditions inevitable in the long term. They argue – or perhaps speculate – that the process of irreversible self-reinforcing changes could in theory start at levels of global warming as low as 2°C above pre-industrial levels, which could be reached around the middle of this century (we are already at around 1°C). They also acknowledge large uncertainty in this estimate, and say that it represents a "risk averse approach".

A key point is that, even if the self-perpetuating changes do begin within a few decades, the process would take a long time to fully kick in – centuries or millennia.

Not just yet. underworld / shutterstock

Not just yet. underworld / shutterstockSteffen and colleagues support their suggestion of a threshold at 2°C through reference to previously-published scientific work. These include other review papers which themselves drew on wider literature, and an "expert elicitation" study in which scientists were asked to estimate the levels of global warming at which "tipping points" for these key climate processes might be passed (I was one of those consulted).

The authors argue that 2°C can still be avoided if humanity takes concerted action to reduce its warming effect on the climate. In a similar way that the "Hothouse Earth" scenario involves huge changes in the climate system with multiple effects of one process leading to another, the concerted global action to avoid 2°C would, they suggest, also involve huge changes in the human system, again with several fundamental steps leading from one change to another.

Personally, I found this an interesting and important think piece that was well worth reading. But since this is not actually new research, why is it getting so much coverage? I suspect that one reason is the use of the vivid "Hothouse Earth" term at a time when everyone's talking about heatwaves. Another is that it's clearly a dramatic narrative, and not surprisingly this has led to some sensationalist articles.

Sun vs permafrost, in Greenland. Adwo / shutterstock

Sun vs permafrost, in Greenland. Adwo / shutterstockWith some exceptions, much of the highest-profile coverage of the essay presents the scenario as definite and imminent. The impression is given that 2°C is a definite "point of no return", and that beyond that the "hothouse" scenario will rapidly arrive. Many articles ignore the caveatsthat the 2°C threshold is extremely uncertain, and that even if it were correct, the extreme conditions would not occur for centuries or millennia.

Some articles do however emphasise the more tentative nature of the work, and some push back against this overselling of the doomsday scenario, arguing that provoking fear or despair is counterproductive.

One thing that strikes me about the scientific literature on "tipping points" is that there are a lot of review papers like this that end up citing the same studies and each other – indeed, my colleagues and I wrote one a while ago. There is a great deal of interesting, insightful research going on using theoretical methods and calculations with large approximations. However, we have yet to see an equivalent level of research in the highly-complex Earth System Models which generate the kind of detailed climate projections used for addressing policy-relevant questions by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Steffen and colleagues have made a good start at addressing such questions, going as far as they can on the basis of the existing literature, but their essay should motivate new research to help narrow down the huge uncertainties. This will help us see better whether "Hothouse Earth" is our destiny, or mere speculation. In the meantime, awareness of the risks – however tentative – can still help us decide how to manage our impact on the global climate.

Richard is Chair in Climate Impacts at the University of Exeter and Head of Climate Impacts in the Met Office Hadley Centre. His undergraduate studies were in Physics at the University of Bristol, followed by an MSc in Meteorology and Climatology at the University of Birmingham. For his PhD, he used climate models to assess the role of the world's ecosystems in global climate and climate change. He has worked in climate modelling since 1992, with a particular interest in the impacts of climate change on ecosystems and the interactions with other impacts of climate change such as on water resources.

This post first appeared on:

Giovanni Federico and Antonio Tena-Junguito introduce findings from a new research project on historical trade data.

Since 2007, the apparently unstoppable growth of world trade has come to a halt, and the openness of the world economy has been stagnating, or even declining. The recent prospect of a trade war is fostering pessimism for the future. Some people are hinting at a repetition of the Great Depression. These historical parallels are fascinating, although somewhat risky. At the very least, one should know exactly what happened to trade in the past (Eichengreen and O'Rourken 2012). This is fairly easy for recent years, but the series available for the pre-1938 period are incomplete, obsolete, and sometimes just wrong. For this reason, we have started a research project on world trade from 1800 onwards. We reported a first set of results in a number of papers (Federico and Tena-Juanquito 2017a, 2017b, 2018a), also summing them up in two previous columns here at VoxEU.org (Federico and Tena-Juanquito 2016a, 2016b). In a nutshell, we have found that:

Trade grew very fast in the 'long 19th century' from Waterloo to WWI, recovered from the wartime shock in the 1920s, and collapsed by about a third during the Great Depression. It grew at breakneck speed in the Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960s and again, after a slowdown because of the oil crisis, from the 1970s to the outbreak of the Great Recession in 2007. The effect of the latter on trade growth is sizeable but almost negligible if compared with the joint effect of the two world wars and the Great Depression. However, the effects might become more and more comparable if the current trade stagnation continues.The distribution of world exports by continent and level of development remained fairly stable until WWI. During the Great Depression, Europe lost more than the rest of the world, and the peripheral countries (and Japan) gained, but these changes were largely reversed during the Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960s. Thus, by 1972 European countries and the 'old rich' (North Western European countries and the US) still accounted for over a half of world exports. Since then, changes in world shares have been large and, at least so far, permanent. The share of Asia rose from about a sixth to a third, at the expense of all other continents. Contrary to a widely held view, the current level of openness to trade is unprecedented in history. The export/GDP ratio at its 2007 peak was substantially higher than in 1913 and the difference is much larger if the denominators include only tradables (i.e. it is the value added in agriculture and industry). Furthermore, openness increased from 1830 to 1870 (the true first period of globalisation) and again from the mid-1970s to 2007, while it broadly stagnated both in the decades during the so-called first globalisation (1870-1913) and during the Golden Age. Needless to say, openness collapsed during the Great Depression, back to the mid-19thcentury level.The trends in gains from trade, as measured with the Arkolakis et al. (2012) formula, mirror quite closely the movement of openness, with peaks in 1913 (6.3% of GDP, for 36 polities) and 2007 (11.5%). These figures are surely a lower bound of total (static) gains, and in all likelihood the difference between estimated and actual gains was larger in 2007 than in 1913.

For the period after 1950, we rely on standard UN data for both GDP and trade, while for pre pre-war years we use our own newly compiled databases. We collected all the available series of GDP at current prices and estimated series of exports and imports by 'polity' (i.e., independent countries' colonies and the corresponding native territories before Western colonisation). Twelve export series start in 1800, and three additional ones in 1813. The number jumps to 28 in 1816 and again to 62 in 1823 and rises to 89 in 1830. The number of import series grows as well, but remains lower in the first half of the 19thcentury (nine in 1800, 23 in 1823, and 50 in 1830). From 1850 to 1938, the database is complete – i.e. it includes series of imports and exports for all existing polities, with few and insignificant exceptions. Their number varies according to the changes in the political map, ranging between 125 and 130 until 1918, and jumping to around 140 after the Versailles treaty.

After 1850, we compute world trade by summing exports by polity, but this method would yield upwardly biased results for the first half of the century. Thus, we extrapolate the 1850 level backwards to 1800 by linking three series for as many time-invariant samples, for 1800–1821 (12 polities), 1823–1829 (62 polities), and 1830–1849 (89 polities). Even the first sample, though small, is representative (62.3% of world exports in 1850), as it includes France, the UK, and the US. The 1823 and 1830 samples are fully representative, accounting respectively for 81.4% and 95.7% of world trade in 1850. None of the previously available series extend so far back in time (they go back, at most, to 1850), nor do they comprehensively cover peripheral countries.

These series, and all data by polity, are now freely available in the Federico-Tena World Trade Historical Database.

Figure 1 The Federico-Tena World Trade Historical Database

Image: Federico-Tena World Trade Historical Database.

For each polity (a total of 149) we provide a separate Excel file, which can be easily retrieved from the website by clicking the corresponding button in the Google map (see Figure 2). It is thus possible to study the trade performance of a single polity or of any group of polities of interest.

Figure 2 Image of the Web Map

Image: Federico-Tena World Trade Historical Database

The set includes eight series, for exports and imports at current and constant (1913 dollars) prices at current and constant borders, for a total of 13,075 yearly data for imports and 14,399 for exports and 109,896 observations. We describe in detail the methods and sources of our estimates and assess their reliability in Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016). This paper refers to our main estimate, which was completed in 2014. Since then, we have revised some series to correct errors and to take into account new research made available to us in the meanwhile (information on these changes can be found here). We intend to periodically update the database to correct mistakes and incorporate the results of future research on trade. The next revision is scheduled for October 2020 and we would be grateful for any suggestions.

The estimation of polity series has required the collection of a number of additional series, which we also publish on the website. In particular, we publish series of 'international' prices for 190 products, as proxied by prices in London or, for manufactures, unit prices of British exports, from 1850 to 1938; of 48 freights rates by product/route from 1800 to 1838; and of exchange rates for diverse years from 1800 to 1938, for 132 countries.

Although our main interest is in aggregate trade, we have collected a substantial amount of information about the composition of trade from a number of different sources. Unfortunately, few recent works group products according to modern categories, while contemporary sources use widely different criteria which prevent any analysis of composition beyond the simple distinction between primary products and manufactures. We estimated series of the share of primary products on imports and exports for a growing number of polities, from 25 in 1820, to 110 after 1850. We use these data to estimate a series of world share of primary products from 1820 to 1938, by linking trade-weighted averages for three different time-invariant samples, starting in 1820 ('1820 sample', with 23 polities), 1830 ('1830 sample', 32 polities) and 1850 ('full sample', with 90-110 polities).

Figure 3 Share of primary products on exports, baseline series, 1820–1938

Image: VoxEU

The share of primary products (Figure 3) has been drifting downwards, from about 65% in the 1820s to slightly above 55% on the eve of WWI, with an acceleration of the trend around 1860. This decline continued, albeit very slowly, in the 1920s, while the share rebounded after 1929 back to the level of the early 1910s. As Figure 4 shows, the aggregate share of primary products on exports declined for both rich countries and the rest of the world.

Figure 4 Share of primary products for export and imports in rich and poor countries

Image: VoxEU

Image: VoxEU

Before 1913, the trend by polity was mixed, but the worldwide share declined because of the change in the specialisation of the US. Primary products accounted for four-fifths of American exports before the Civil War and for a third on the eve of WWI and in the interwar years. If the share of primary products on US exports had remained constant since 1850, in 1913 the overall one would have been 62.7% rather than 62.3% – with an increase of 0.45 percentage points instead of the actual decline by 6.3 points. The decline in the share on exports by polity continued in most countries until 1938 – the increase in the worldwide share reflects the growing share of world exports of primary producing polities.

Figure 4 highlights another significant divergence from the conventional wisdom. World trade during the first globalisation was not a simple vertical exchange of primary products from the periphery with manufactures from the core countries. As expected, primary products accounted for most exports of poor countries (on average 86.1% from 1850 to 1938) and for most imports of rich countries (73.6%), but they accounted for about a third of exports from rich countries (38.0%) and for slightly less than half of imports of poor countries (45.5%).

Of course, an analysis based only on the aggregate share of primary products barely scratches the surface of the issue. Unfortunately, estimating the changes in composition of world trade, even at the simplest one-digit level, would need a massive research effort. While we await this, our database and the parallel database on aggregate bilateral trade (RICARDO) offer scholars a very valuable resource for historical quantitative analyses of trade – historical comparisons might be useful for understanding current and future trade trends.

Giovanni Federico, professor of Economic History, University of Pisa. Antonio Tena-Junguito.

This first appeared in the Agenda blog.

Image credit: Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)